This article expands on a documentary produced by DocuReal that revisits one of the most baffling and emotionally charged criminal mysteries in modern British history: the murder of Jill Dando. Twenty‑five years after that spring morning in 1999, the questions remain stubbornly the same — who killed Jill, why was she targeted, and why has justice never been satisfactorily achieved? I wrote this piece to walk you through Jill’s life, the day she died, the chaotic investigation that followed, the arrest and trial that gripped the nation, and the unresolved legacy that continues to haunt colleagues, family, investigators and the public.

Introduction: Why Jill Dando’s Murder Still Matters

When someone recognizable and beloved is taken in public, the shock reverberates beyond family and friends — it becomes a national grief. Jill Dando was more than a familiar face on television. She embodied a particular kind of warmth and accessibility that made people feel she was one of their own. The brutal, seemingly motiveless killing of a presenter who built a career on helping others — particularly through the BBC programme Crimewatch — produced an unusual cocktail of outrage, sadness, confusion and fevered speculation.

Two and a half decades later, this case offers lessons about investigative practice, media pressure, forensic reliability, and the consequences of crafting a narrative before the full evidence is known. The murder is also a study in the vulnerability of public figures, the limits of eyewitness testimony, and how a single tiny particle of forensic evidence can determine the fate of a life.

Who Was Jill Dando? The Life Behind the Smile

Jill Dando was born on 9 November 1961 in Weston‑super‑Mare, Somerset. She grew up in a modest, devout Baptist household, the younger of two children to Jack and Winifred Dando. From her earliest years Jill displayed the traits that would later endear her to millions: warmth, generosity, and an easy knack for connecting with people. She did not take the conventional university route; instead she trained in journalism at a local college and joined the paper where both her father and brother worked.

Her career progressed step by step. She worked on regional radio and television for the BBC, delivering bulletins and building a reputation as a capable and engaging broadcaster. In 1988 she moved to London. By 1989 she had joined BBC Breakfast, where a pivotal relationship with Bob Wheaton — then news editor — helped guide her professional advancement. Wheaton was both partner and mentor, promoting Jill into a broader range of presenting roles: from news bulletins to holiday shows, antiques programming and programmes of faith like Songs of Praise. The blend of competence, curiosity and approachability quickly made her a household name.

In 1995 Jill started co‑presenting Crimewatch with Nick Ross. That role placed her literally at the heart of the public’s engagement with policing and crime solving. Crimewatch reconstructed crimes, appealed for witnesses on camera and helped secure convictions. For many viewers Jill’s role on that programme represented trust: she promised to help the vulnerable and to assist the public and the police in finding justice.

Public Attention and the Cost of Visibility

Being prominent on television brings more than admirers. Female presenters often receive unwelcome and, occasionally, threatening attention. Jill and some of her colleagues, like Alice Beer, received unsettling letters that included threats — reportedly acknowledged by the BBC, but with unclear follow‑up. The culture at the corporation at the time meant such threats were sometimes not prioritized as seriously as they might have been. That context would later feed into questions about whether more could have been done to protect prominent staff, and whether such threats were fully investigated prior to the murder.

The Day Everything Changed: 26 April 1999

Monday 26 April 1999 began like any other spring day. Jill had been living with her fiancé, Dr Alan Farthing, and had been in the process of selling her house in Fulham. On the morning in question she went to Hammersmith to shop and was captured on CCTV moving about in an ordinary, unremarkable way. There were no clear signs she was being followed or that she had been targeted.

After shopping Jill returned to her house on Gowan Avenue to collect documents faxed to her by her agent, John Roseman — papers she needed before heading into the BBC where she was due to read the news that evening. What happened between the moments she walked back to her door and when she was discovered lying on her doorstep would become a fiercely contested and heavily scrutinized timeline.

Discovery and Immediate Aftermath

At around 11:32 a.m. Jill was shot once in the head at close range and collapsed in the area immediately outside her front door. Neighbours, passersby and eventually emergency services converged on the scene. A frantic call to the ambulance service captured the initial shock of discovery: “She’s collapsed in her door. There’s a lot of blood… I don’t think she’s alive.” In the early chaotic hours, details were fragmentary and the crime scene was compromised by the sheer number of people who arrived and attempted to help. Many later argued that this contamination proved costly; nevertheless, until proven otherwise, the priority was to identify witnesses and preserve what could be salvaged.

Jill’s death was pronounced at the scene. The nature of the attack — a single shot fired at point‑blank range — suggested a planned, deliberate killing rather than a spontaneous assault. But a planned murder typically leaves a trail: CCTV footage, a witness who saw a suspect up close, forensic traces. In Jill’s case that trail was thin.

Investigative Challenges: Sparse CCTV and Confused Witnesses

In 1999, CCTV existed but was neither ubiquitous nor of the quality we assume today. Gowan Avenue offered very little in the way of clear camera coverage. Investigators turned, therefore, to human memory — eyewitness accounts — as the primary source of leads. And that is where the first major difficulty emerged: witnesses who differed in their descriptions, contradicting each other on basic details like height, complexion, clothing and gait.

One neighbour reported hearing screams and seeing a man of about six feet leaving Jill’s path. Another driver described having to brake suddenly to avoid a person running across the road. Some witnesses said the fleeing man was sweating profusely and appeared to have been running; this detail would later be pivotal. But witness testimony can be unreliable, particularly in the heat of a shocking moment. Conflicting accounts made it hard for detectives to be certain about who they were looking for.

Crimewatch, the Reconstruction, and an Outpouring of Public Interest

Crimewatch, the programme Jill helped present, mounted a substantial reconstruction, broadcasting to millions in the hope of encouraging witnesses to come forward. The public response was enormous. For the programme and for Jill’s colleagues, approaching the case as both a professional mission and a personal tragedy made the reconstruction especially charged. The broadcast did help secure additional leads, but it also intensified speculation and contributed to a media environment that demanded a quick resolution.

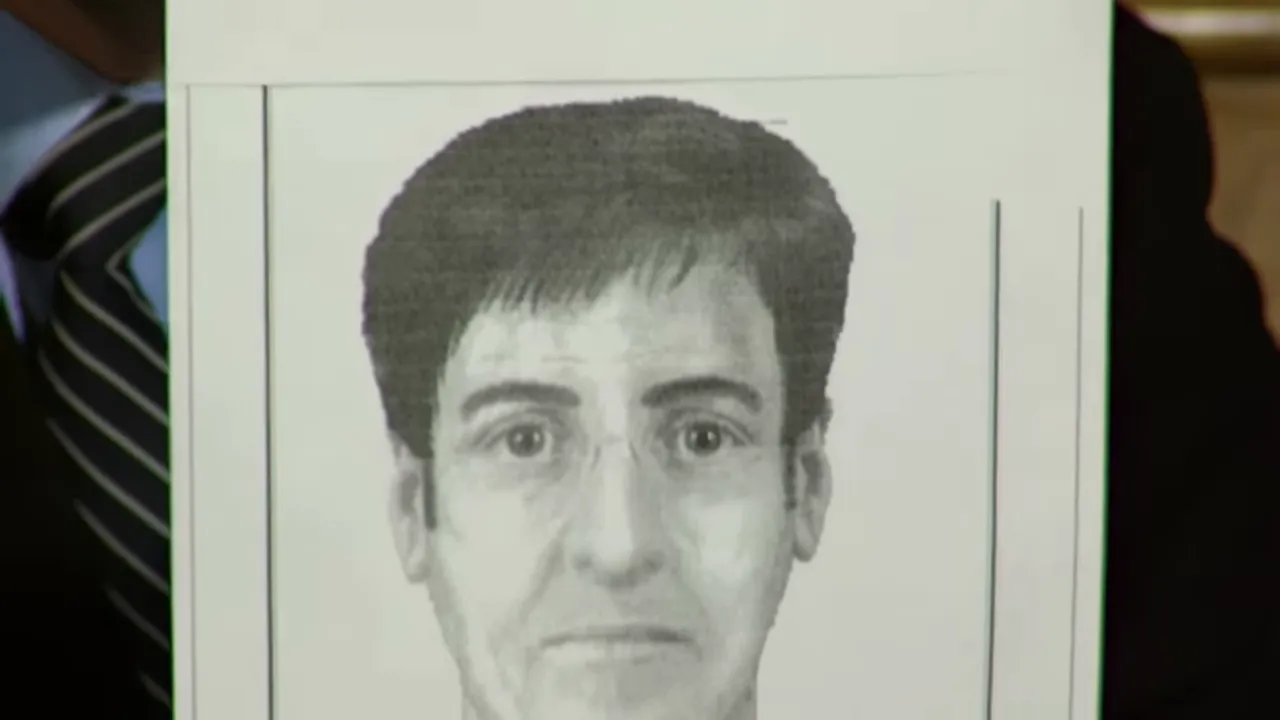

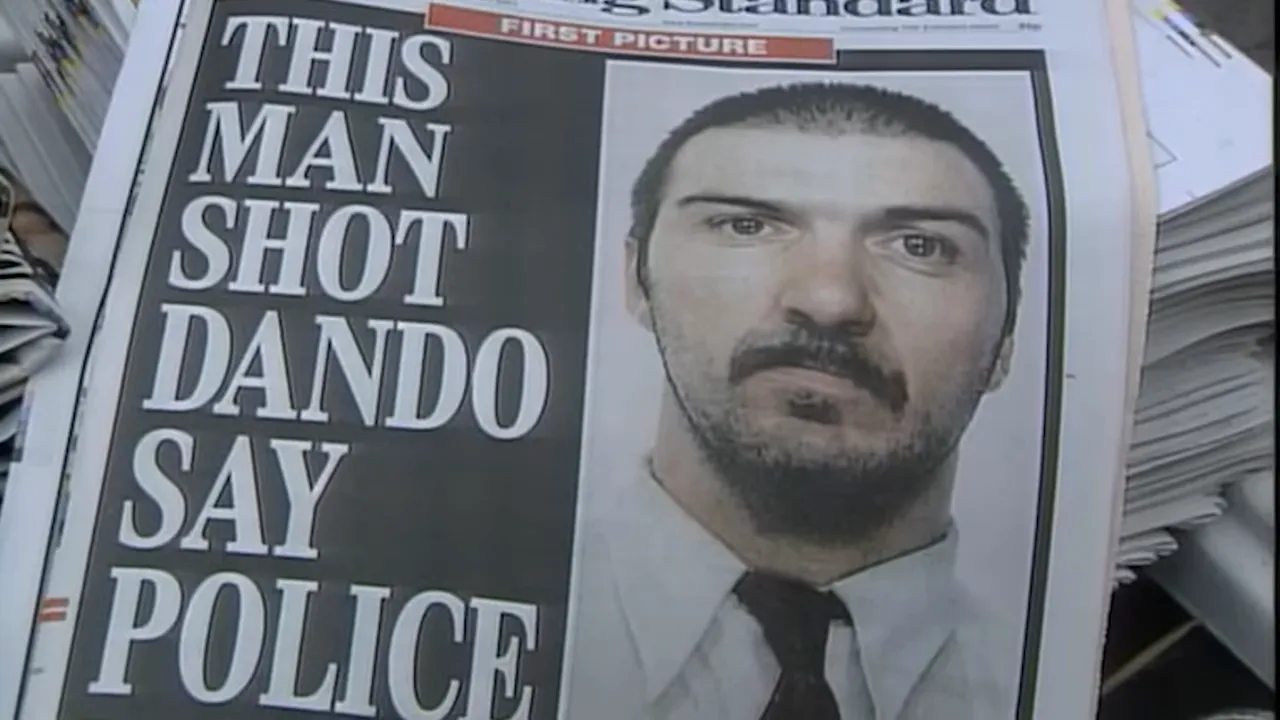

Faces and Leads: The EFIT and Witness Identification

One crucial witness — the man at the bus stop on Fulham Palace Road — drew investigators’ attention because of a detail that seemed unusual: the suspect was sweating so heavily that it reached into his collar. This visual focus allowed police to create an EFIT (a computer‑generated facial composite) which they released publicly. That composite became a central image in the hunt and in many ways crystallized the direction police were inclined to follow.

Local residents were generally supportive of the police work and expressed a shared desire for the killer to be found. But even with an EFIT and a motivated public, the lack of unambiguous forensic or technological evidence meant that investigative momentum depended on human memory, chance sightings, and the slow collation of circumstantial leads.

Possible Motives and Early Theories

From the early days investigators and journalists explored multiple possible motives. Unease that Jill's work on Crimewatch might have made her a target was an obvious hypothesis: after all, Crimewatch had been instrumental in helping to convict dangerous criminals. Some suggested a link to a jailed offender, or that she had been targeted by someone seeking revenge for having been exposed by the programme.

Another strand of speculation connected Jill’s humanitarian work — including a recent broadcast appeal on behalf of Kosovo refugees — to geopolitical retaliation. In the immediate aftermath, rumours circulated that Serbian extremists had phoned the BBC claiming responsibility. It was a plausible notion in the climate of late‑1990s Balkan violence, and it fed a broader media narrative. But that claim never materialized into verifiable intelligence or a credible admission, and investigators were unable to substantiate a foreign political motive.

Why Motive Matters — And How It Evaporated

Motive is a compass for detectives. Without it, inquiries must focus on opportunity and means — who had access to the victim, who knew her movements, who had cause to harm her. Investigators scrutinised Jill’s personal relationships, financial dealings, and professional interactions. They examined ex‑partners, current partners, agents, and colleagues — precisely the type of thorough inquiry homicide detectives are trained to perform. But as the list of possible suspects grew broader, the clarity of a single compelling theory slipped away.

Turning Toward a Local Suspect: Barry George

Investigators eventually focused much of their attention on a local man named Barry Michael George. George was known in the area and had a history of unsettling behaviour. He had prior convictions, including for sexual assault, and had developed a reputation as a stalker of women and a fantasist. He adopted alternate identities — at times styling himself with flamboyant personas — and collected images and monitors of television presenters among reels of undeveloped film found in his home.

Evidence Gathered at His Home

Police searched George’s flat — a cluttered, chaotic dwelling a short distance from Gowan Avenue — on multiple occasions. Investigators found camouflaged clothing, a gun holster, magazines, lists referring to weapons prices, extensive rolls of undeveloped film depicting hundreds of women, and material relating to television personalities, including Jill. These items established a troubling pattern of obsession and proximity, and they made George a person of interest.

Under surveillance and after intensive questioning, George was arrested and charged with Jill's murder less than a year after the killing. The case that went to trial featured a mixture of witness testimony and forensic science. Yet the forensic evidence was sparse and controversial. The prosecution's case hinged heavily on one small piece of physical evidence: a microscopic particle of firearms discharge residue (FDR) found in Jill’s hair around the bullet wound, which matched a particle found on a coat recovered from George’s flat.

Trial: Conviction and the “Golden Nugget” of Forensic Evidence

When the trial reached court, the prosecution argued that the presence of that identical particle linked George directly to the firearm that killed Jill. For jurors, the presence of a particle that matched material from the scene and traces on the defendant's property carried persuasive weight. The crowd of circumstantial indicators — his proximity, history, fixation on TV figures, the items found in his home, and witness identifications — layered together to create a narrative prosecutors felt a jury could accept.

In 2001 the jury found Barry George guilty of murder and he was given a life sentence. For many, the conviction offered closure and a measure of relief. Jill’s family and her colleagues at the BBC hoped that a culpable person had been identified and punished for a shocking, senseless death.

Questions that Followed the Verdict

Yet from the moment of conviction, scepticism persisted. Defenders of George argued that the case was circumstantial and that the forensic linkage of the tiny particle — the "golden nugget" the prosecution relied upon — might not be as definitive as it had seemed. How reliable was that single particle as proof of firing the murder weapon? Could contamination or transfer account for its presence on a coat? Were witnesses certain in their identifications?

Appeal, Retrial and Acquittal: Forensics Under the Microscope

After serving around eight years of his sentence, George succeeded in securing an appeal and retrial. The Court of Appeal ordered a retrial in 2007 or 2008 after concluding that the original trial might have been influenced by forensic evidence that had not been properly handled or contextualised for jurors. Central to the appeal was the conduct of the forensic process and the possibility that the FDR particle could have been transferred onto George’s coat through innocent secondary contact or contamination in the laboratory — a possibility made credible by mistakes in evidence handling.

Mannequins, Mistakes and Reasonable Doubt

One of the most damaging revelations was procedural: George’s coat had been placed on a mannequin and photographed before the coat received a full forensic examination. The mannequin in question had previously had other garments placed on it. Given the prevalence of guncrime in London at that time and the presence of gunshot residue in many environments, the chain of custody and the sequence of evidence processing matters immensely. The Court of Appeal concluded that the original jury could have been misled about how conclusively the particle linked George to the firearm. The particle could have come from another source — transferred in the lab or via other contact — and it did not necessarily prove that George fired the weapon.

At retrial in 2008, prosecutors agreed that the FDR evidence should not be presented in the same way and that the jury should be excluded from weighing that particle as they had in 2001. Without that strand of forensic evidence, the case returned to being largely circumstantial. Former jurors and observers had already said that, for many of them, the firearms residue had been the linchpin of the conviction. With that removed, the retrial jury returned a not guilty verdict and Barry George was acquitted and released.

Aftermath, Reflection and Criticism of the Investigation

The acquittal reopened wounds. For Jill’s family and supporters the idea that no one would be jailed for her killing felt intolerable. For others, the acquittal highlighted legitimate concerns about forensic practice, investigative tunnel vision and the dangers of confirmation bias when police build a case around a single narrative. The investigators had followed a path that led to a suspect who fit the local pattern of concern, but the possibility remained that they had been searching for proof rather than truth.

There were practical criticisms too. The crime scene had been overwhelmed in the first chaotic hours by neighbours, paramedics and passersby who wanted to help but may have unintentionally destroyed or contaminated evidence. The lack of robust CCTV, the inconsistent witness descriptions and the limited physical traces made the investigation especially vulnerable to error. When a microscopic piece of residue becomes the pivotal link, it also becomes a point of enormous scrutiny; the revelation of procedural missteps in handling the coat was therefore catastrophic for the prosecution’s case.

Was the Investigation Professional, Thorough and Honest?

The official conclusion was that the investigation had involved dedicated professionals who worked long hours under intense pressure to resolve an extraordinary case. Yet critics argued that detectives exhibited a degree of tunnel vision: once they saw a pattern pointing toward a single suspect, they may have given less weight to alternative lines of inquiry. The distinction between “evidence that proves” and “evidence that tends to suggest” is critical in homicide work, and many commentators believe investigators crossed that line.

It is important to be measured in that critique. Homicide investigations are inherently hard. Detectives rely on witness memory, forensic science and painstaking detective work under tight deadlines and enormous public scrutiny. That said, mistakes do matter and can change the fate of defendants and the ability to secure the correct perpetrator. The Dando case has become a cautionary tale in investigative procedure and forensic reliability.

Other Theories: Conspiracy, Revenge, and the Missing Claim

From the start, the case spawned numerous theories. Some linked the crime to foreign political groups because of Jill’s Kosovo appeal; others suggested a hit ordered by a jailed criminal who had lost because of Crimewatch's assistance to police. High‑profile suspects were floated in the press — from Balkan hitmen to revenge plots — but none produced verifiable evidence.

One recurring question is why, if the killing were politically motivated or part of a revenge hit, there was no claim of responsibility. Terrorist groups often claim attacks for propaganda value. The silence and lack of demand in this instance make political or professional retaliation less likely. That said, absence of a claim does not prove innocence nor does it definitively exclude an external actor. But the balance of probability and the vectors of investigation led police to think the perpetrator was local or someone who knew Jill’s patterns.

Public Reaction, Mourning and the Funeral

The national mood in the weeks after Jill’s death was one of stunned grief. Dozens of bouquets were left at her home, colleagues and viewers were stunned, and the media attention was relentless. Her funeral brought colleagues, friends and family together in a public display of mourning that many compared to the public reaction to Princess Diana’s death — not in scale but in the intensity of the emotional response.

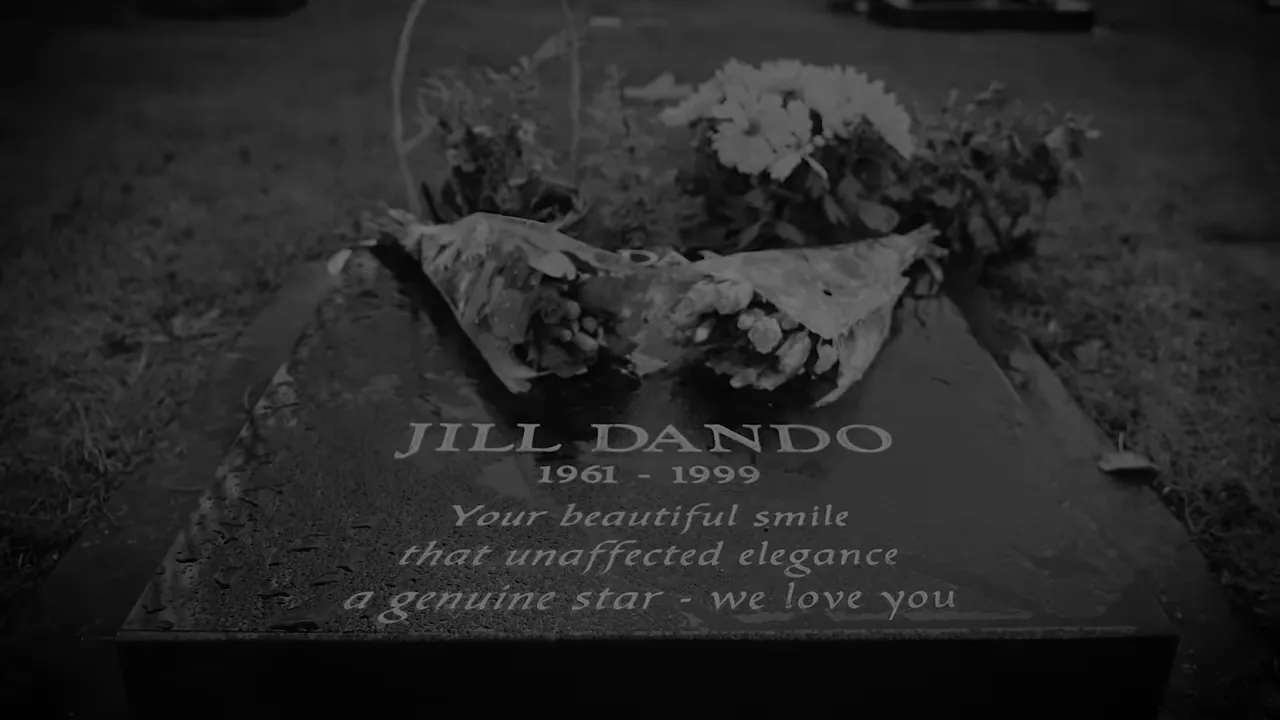

Jill's coffin was accompanied by her fiancé, Alan Farthing, her father Jack, and her brother Nigel. The Reverend who addressed mourners spoke of a life that had been entering “a new, exciting, fulfilling age” until that fateful moment on Monday 26 April. For many people the memory of the warm face on television and her signature sign‑off — “Sleep well” — made the loss feel deeply personal.

The Legacy: Media Safety, Forensic Process and Unanswered Questions

Jill Dando’s murder changed how certain parts of the media and police think about presenter safety and the scrutiny of forensic process. The case highlighted the hazards of placing forensic evidence on a pedestal without rigorous review of chain of custody and contamination risk. It also drew attention to how intense media pressure can shape investigative priorities and public perception.

The case has also left a moral and emotional residue: a family without finality, colleagues who remain haunted by their inability to answer the enduring “why,” and a public that continues to be fascinated by high‑profile unsolved crimes. Jill’s name, for many, still conjures a case that is unresolved, and that unresolved status fuels curiosity and, for some, frustration with the justice system.

Has the Crime Been Solved? The Cold Trail

Officially the murder is unsolved insofar as no one is currently serving a prison sentence for the killing. Investigators have periodically reviewed the case, and forensic techniques have evolved since 1999. Yet the combination of a compromised crime scene, limited CCTV, conflicting witness testimony and the passage of time makes any future prosecution far more difficult. The physical evidence that might have tied a perpetrator definitively to the scene was either never recovered or was jeopardised by human activity at the scene and procedural missteps in evidence handling.

It remains possible that someone with detailed knowledge of Jill’s movements committed the crime, but proving that beyond reasonable doubt now would require either a confession, new forensic material, or some new information that links a suspect incontrovertibly to the act.

The Human Dimension: Remembering Jill

Above all the forensics, the EFITs, the courtrooms and the theories, Jill Dando’s story is a human one. Colleagues remembered her warmth and her ability to connect: “She was very much the girl next door… generous of spirit, inquisitive and likable.” Those who worked with her recall not only a professional presence but a personality the public felt they knew like a neighbour. Her manner, the small personal touches such as the way she signed off Crimewatch with “Sleep well,” made her feel like a friend to millions.

That is why the absence of finality matters so much. The family has been left with a puzzle — a question of where, exactly, the nexus of culpability lies. Jill’s brother observed publicly that she might have been in the wrong place at the wrong time, and many others have echoed that sentiment. But the depth of attachment the public felt towards her makes the lack of resolution particularly painful.

Lessons from the Case: For Investigators and the Public

There are several clear lessons that come from re‑examining Jill Dando’s murder twenty‑five years on:

- Chain of custody matters: The sequence in which forensic items are handled, examined and documented can be decisive. The missteps around George’s coat illustrated how procedural lapses can undermine otherwise plausible forensic links.

- Forensics is powerful but not infallible: Microscopic particles can be persuasive, but they must be interpreted cautiously. Transfer, background prevalence and contamination are real risks.

- Witness testimony must be contextualised: Human memory is fallible. Conflicting accounts can mislead investigations if not carefully weighed against objective evidence.

- Media pressure influences investigations: High‑profile cases attract attention that can be constructive (more witnesses) but also distortive (rush to arrest a suspect or to craft a single narrative).

- Protecting public figures: The case prompted reflection about the duty of employers and broadcasters to take threats seriously and to provide appropriate protections to visible personnel.

Why the Case Still Fascinates

Unsold mysteries have a persistent cultural power. They invite endless re‑examination because they remain open-ended: a missing piece could still be out there. Jill Dando’s murder combines the elements that tend to hold public attention — a charismatic, beloved victim; a violent and senseless act in a quotidian setting; an apparently ordinary local man arrested and later acquitted; forensic minutiae that determine a life sentence; and an absence of a neat conclusion.

Add to that the human stories — colleagues who still miss her, a fiancé who lost his partner, a brother who lost a sister — and the public interest becomes not only about “who did it?” but about how the justice system handles tragic, high‑profile crimes. That mixture of human sorrow, institutional fallibility, and enduring doubt is the emotional core of why Jill Dando’s case will not easily fade from public consciousness.

Conclusion: The Puzzle Unsolved

Twenty‑five years after April 26 1999, the nation still holds its breath. Jill Dando was a beloved broadcaster whose life was cut down in the open, outside the door of the home she no longer lived in full time but visited for paperwork, clothing or convenience. The investigation that followed was exhaustive but flawed in ways that matter. A conviction was achieved, later overturned, and the question of who actually killed Jill — and why — remains a persistent, painful mystery.

That unresolved status carries consequences beyond the intellectual: for Jill’s family it means enduring grief without judicial closure; for the public it means an unresolved, haunting chapter in the story of modern British crime; for police and forensic practitioners it represents a cautionary tale on the limits of evidence and the imperative for procedural care. Cases like this force us to confront uncomfortable truths about human error, the fragility of memory, and the immense responsibility that falls upon those who investigate and prosecute.

As long as new techniques in forensic science emerge, or as long as someone with crucial information comes forward, there remains a sliver of possibility that the answer will one day be found. Until then, Jill’s death stands as a reminder of the complexity of truth in criminal investigation, and the cost borne by victims and their families when that truth proves elusive.

Further Reading and Reflection

If you want to explore the case in greater depth, consider the following avenues: detailed timelines of the investigation, court transcripts from both trials and appeal, forensic reviews concerning firearms discharge residue, and contemporary commentary from journalists who covered the trial and the appeal. The case has been revisited by documentary makers, legal commentators and investigative journalists, each offering a perspective on the mistakes, the strengths and the human stories involved.

Above all, when approaching this material, I encourage readers to remember the person at the centre: Jill Dando — not merely a symbol of a case, but someone who had family, friends, colleagues and a life that mattered to many. To reduce her to an object of speculation is to miss the human tragedy that underlies every true crime story.

Jill's story remains unresolved, and that absence of closure is itself a kind of testimony: to how fragile certainty can be even in a world saturated by surveillance, science and sensational reporting. It is my hope that a clear answer will one day emerge. Until then, remembering Jill honestly and critically engaging with the facts of the investigation are the best ways to honour both her memory and the demands of justice.

0 Comments