This article is based on the documentary produced by Unseen and is written from my perspective as the narrator of that story. I tell this account not just to replay events, but to explain how a single night's violence shattered a family and a community, how a serial killer's ego prolonged his freedom for decades, and how modern forensic science and vigilant police work finally ended his reign. This is the story of the Otero family, the shadow of BTK across Wichita, and of one boy—fifteen years old—who would spend the rest of his life chasing justice for the people he loved.

Introduction: A Family, a City, and a Name That Would Terrorize Them

On the morning of January 15, 1974, my subject—15-year-old Charlie Otero—left for school like any other teen. He was driven by a simple aim: to do well, make his parents proud, and live a life shaped by the love he witnessed at home. His parents, Joseph and Julia Otero, were the pillars of a household filled with warmth and promise. But that afternoon would mark the beginning of a nightmare that would reverberate through Wichita, Kansas, for more than three decades.

That night, Charlie returned to find his home transformed into a crime scene. Four members of his family were bound, gagged, and strangled. The violence was calculated and personal. The officers who entered the house looked shaken—what they saw would shake anyone. The murders were brutal, intimate, and inexplicable. In the weeks and months that followed, the city locked its doors and hoped the events were isolated. As you’ll read, they were not.

January 15, 1974 — The Otero Family Is Destroyed

Joseph and Julia Otero were relatively new to Wichita. Joseph, a military man with energy and a zest for life, and Julia, a loving mother who cared for everyone around her, were raising five children with hopes and dreams. Charlie, the eldest at 15, was exemplary: good grades, responsible, protective of his younger siblings. He had a simple wish—make his parents proud.

That afternoon it had been snowing, and Charlie had convinced his father to drop him off at school early so he could attend an early study hall before an exam. His siblings Danny and Carmen were in the car with them. After school, Charlie walked home with two younger siblings, eager to share the news of a perfect test score. The first sign that something was wrong was small and domestic—a gate open, the family dog wandering, a purse left on a stove.

He called out and, at first, thought it was a bad prank. Then he found his parents.

"As soon as I touched him, I knew they were dead. I could smell the fear and the pain that they had gone through. I could feel it all in the room."

Joseph lay on the floor with a belt around his neck. Julia was motionless nearby, bound. Charlie called for help, but the phone line had been cut. He took his siblings to a neighbor and begged them to get help. When officers finally examined the home, they found nine-year-old Joey Jr. bound in his room with a bag over his face and signs in the carpet showing the killer had sat down to watch the boy. In the basement, a police officer bumped into what he thought was a punching bag—only to find 11-year-old Josephine hanging from a pipe. She had been abused prior to death.

The scene destroyed Charlie’s faith in the world. He later said that in that moment he thought, "There is no God. I hate God. I hate the world." The brutality felt inexplicable—who would choose this family? Why them? At first, investigators suspected a drug-related robbery gone wrong. Wichita clung to the hope that this was a one-off. That hope evaporated quickly.

April 4, 1974 — The Pattern Emerges

Just three months later, 21-year-old Catherine Bright was found brutally stabbed in her home—only two miles from the Otero house. Initially, police didn’t connect the murders: the cause of death differed (strangulation versus stabbing). But there were disturbing consistencies. Nylon stockings bound Catherine; the knots were square knots—just as at the Otero scene. In both crimes, the telephone line was cut prior to entry. A composite sketch of a suspect was produced with the help of Catherine’s brother Kevin, who had seen the assailant. Newspapers across Kansas published the sketch and tips poured in, but no solid lead emerged.

By the end of 1974 the collective fear in Wichita was no longer hypothetical. The pattern suggested a perpetrator who was methodical about binding and gagging victims, who used household items like stockings and was comfortable cutting phone lines, escaping before arrival. That pattern would grow as more victims were claimed over the next few years.

The Emergence of a Name: B.T.K.

In October 1974 a man confessed to the Otero murders. Newspapers carried the story and Wichita breathed a tentative sigh of relief. Then an anonymous phone call directed a reporter to the library where a letter and an engineering book were left. The letter read, in part:

"I did this, I did it myself, I did it alone, so let's set this straight."

It included details only someone who’d been in the Otero house could know—specifics like how Josephine "was hanging by the neck in the northwest part of the basement, hand tied with bind cord, noose with four or five turns." The writer taunted the authorities for their supposed failures and signed off with a coded threat.

"The code words for me will be 'Bind them, Torture them, Kill them.' B-T-K."

He claimed to be "a serial killer to be." It was the first time the killer—who would later be universally known as BTK—claimed his moniker in connection with the crimes. He vanished again for decades. The letter suggested an appetite for control, a desire for recognition and ownership over the narrative. BTK wasn’t merely committing murders; he wanted credit, notoriety, and a psychological advantage.

1975–1979: A City on Edge

From 1975 through the late 1970s, BTK’s presence continued. Survivors and families were left to carry an unimaginable weight. Charlie, sent to New Mexico with siblings to live with an uncle, carried a different kind of burden. He told me later how he spiraled: PTSD, substance use, constant hypervigilance. He saw life in fragments—shorn of the ordinary pleasures a teenager usually experiences.

Meanwhile, other homes were targeted. In March 1977 Shirley Vian, a single mother of three, was found with a bag over her head and a noose around her neck. Her five-year-old son, Steve, witnessed the attack and ran for help. The memory of that day would burn in his mind forever. In April of that year, another woman was strangled. The killings were concentrated geographically, and the pattern of tying, binding, and cutting phone lines remained.

By mid-1977 the city’s headlines were stark: multiple homicides, no solid leads. Police were frank in interviews: they had "no solid leads at all." The fear spread like an infection—neighbors locking doors, parents not leaving children alone, a pervasive anxiety in the community. For survivors like Charlie, the killer’s continued freedom prolonged the trauma.

Victims and Survivors: The Human Cost

When we talk about serial killers in public discourse, we often focus on numbers: seven, ten, thirteen victims. But each number masks a universe of humanity. The Oteros—Joseph, Julia, Joey Jr., Josephine—were real people with names, aspirations, friends, churches, jobs, and futures. Catherine Bright had family who loved her. Shirley Vian was a mother. Each life taken left ripple effects—children orphaned, relatives haunted, communities divided.

Steve Ralford, who as a boy watched his mother murdered, said years later something that pierced me: BTK "didn't just kill his mother. BTK really killed him too." That line captures the paradox of survivors' existence. In surviving a violent, intimate crime, a child or family member does not simply return to baseline. Their world is remade around the absence, and they carry wounds that are invisible and persistent.

How Survivors Cope—And Don’t

Some survivors internalize guilt or rage. Charlie, for much of his young adult life, thought in terms of violence and vengeance. He dropped out of his earlier plans and became a drifter—riding a motorcycle, stealing to survive, consumed by the idea that he should have been home that day. If he had been, perhaps things would have changed. That “if only” can become a corrosive force.

Steve, meanwhile, battled despair and the desire to die. Both men found themselves untethered, living in the shadow of what happened rather than in the light of what might have been. And then time did what it does: it passed. But the case did not close for the city of Wichita, and the killer’s ego eventually led him back into the spotlight.

BTK’s Silence—and His Need to Be Known

For decades, BTK was silent. After 1977 the killer faded from public communication. For years the only whispers were the unsolved cases themselves—headlines, anniversaries, and the memory of families left behind. But in 2004 the killer re-engaged with the world in a way that would ultimately seal his fate.

The media were producing stories on the 30th anniversary of BTK’s first murder. Someone was also writing a book. That stirred something in the killer. He did not like competing attention. So he resurfaced, delivering letters, puzzles, photos, and mementos to the press and to police. The communications included a driver's license that had never been located, photographs taken by the killer at a victim’s scene, and chilling artifacts—dolls wrapped in bondage identical to the bindings used on victims.

"How many people do I have to kill before I get my name in the paper?"

That line is a window into BTK's psychology: he sought recognition and used violent ritual as his signature. The letters, the puzzles, and the props were not mere taunts—they were invitations. They invited law enforcement into a game he thought he controlled. Police and the FBI recognized a strategy: keep him communicating, and he will eventually make a mistake.

2004–2005: The Killer Returns, and the Investigation Turns

Between March 2004 and January 2005, Wichita police received five separate communications from BTK. Each release of information to the public was, in part, designed to speak directly to him. The idea was simple: appeal to his ego and evidence-seeking impulses. Make him feel important and watched. Keep him engaged long enough to misstep.

On January 25, 2005, BTK crossed a line. He left a cereal box in a Home Depot parking lot. Inside was a letter and, crucially, a floppy disk. With the disk, BTK believed he was handing over an untraceable way to communicate, a relic guaranteed to hide metadata. He even asked police outright:

"Can you trace a floppy disk? Please be honest."

BTK assumed law enforcement would be as smugly candid as he. He believed the police would admit the disk could not be traced and that he could continue to control the narrative. The officers answered deceptively: "No, it cannot be traced." But they were not entirely truthful. They had, for the first time, another break: surveillance video from the Home Depot parking lot. The video was poor, but it captured a vehicle. One investigator immediately recognized the make: a cheap Jeep Cherokee. It was the first evidence BTK had not intended to give police.

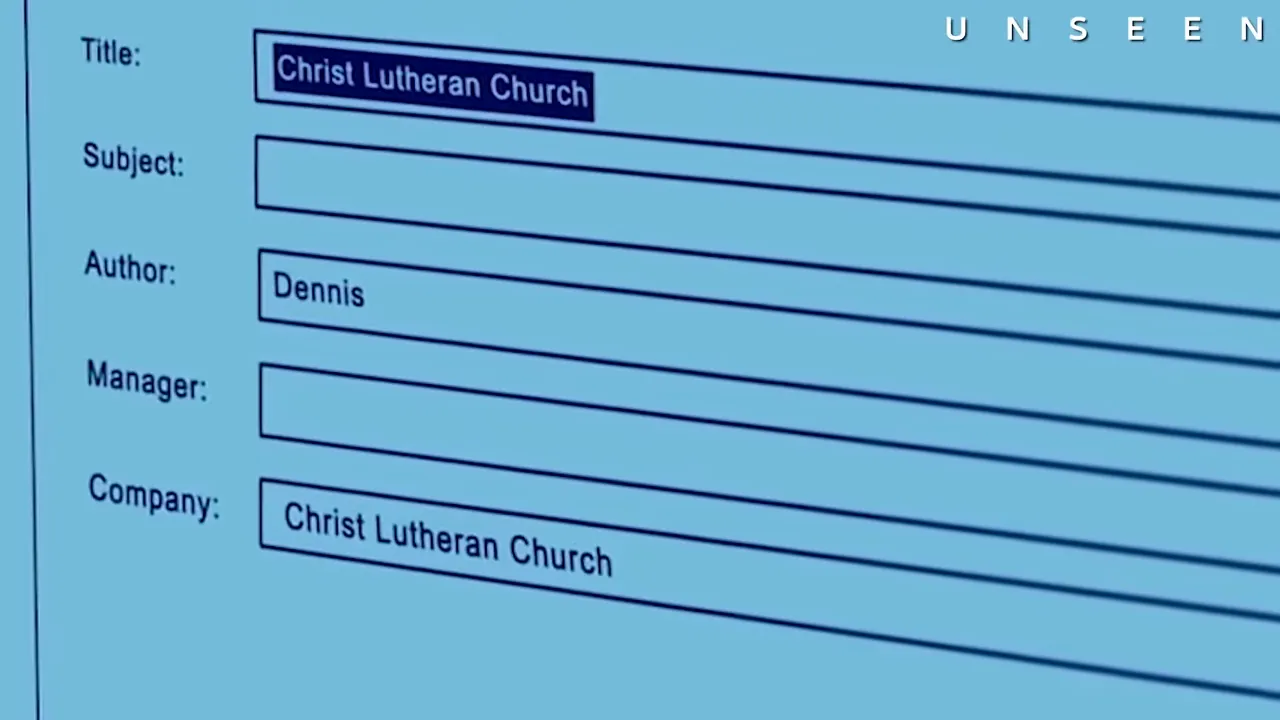

The Floppy Disk — A Fatal Mistake

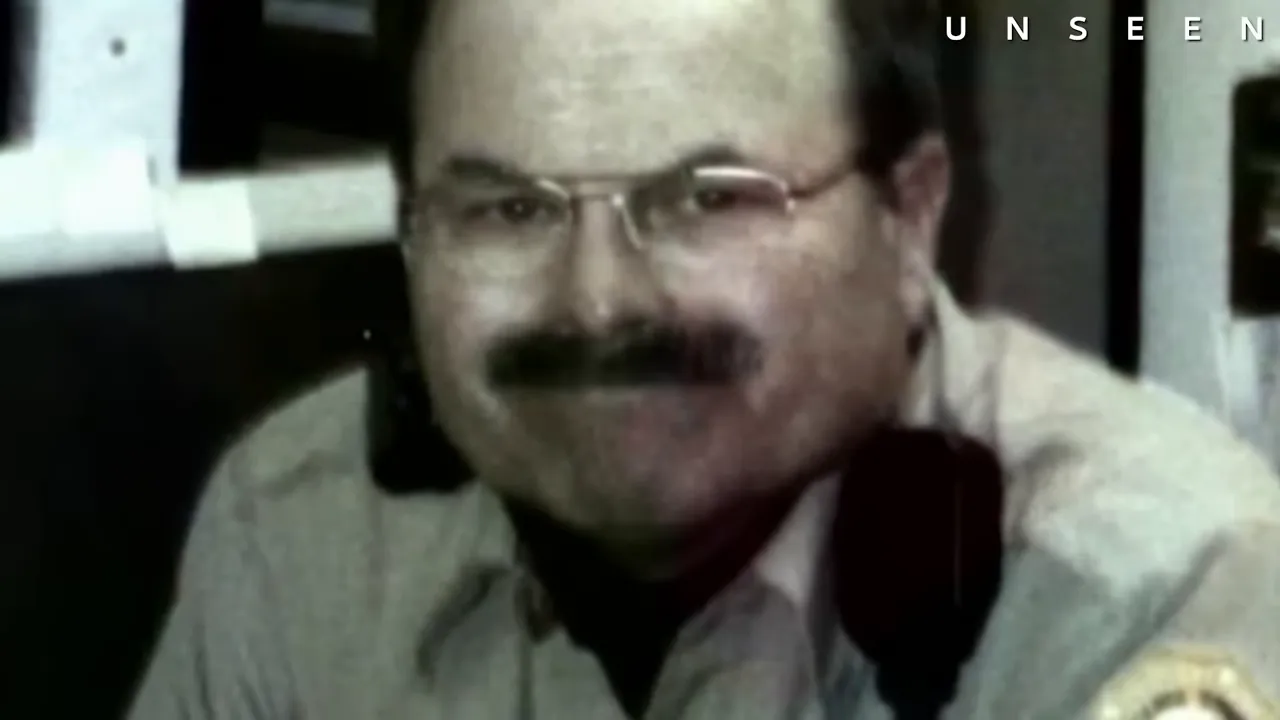

Days later the floppy disk arrived at the department. Forensics analyzed it quickly. Hidden inside the file metadata were references to a registered user: "Dennis," and an organization name: "Christ Lutheran Church." A simple search connected the organization to a man named Dennis Rader. The lead was shocking because Rader did not fit the common stereotype of a serial killer at first glance. He was a church president, a cub scout leader, a seemingly ordinary and active member of his community. He worked for the city as a compliance officer and had once worked for ADT installing alarm systems. The idea that he taught others how to tie square knots only added to the chilling nature of the discovery—what had once been an ominous detail now had a face attached.

Investigators were cautious. It felt too simple. They set silent surveillance, placed him under 24-hour watch, and sought corroborating evidence. They returned to preserved items from the 1974 crime scenes. The remarkable foresight of the original crime scene investigator—who had cut up a pillowcase and used small swatches, preserved for years—proved invaluable. One of those swatches, when tested with modern DNA techniques, yielded a genetic profile.

Forensics, a Pap Smear, and the Breakthrough

In a move that drew both attention and ethical scrutiny in the public eye, investigators took a constitutional, court-authorized step: they obtained a DNA sample indirectly via Rader’s daughter. She had been a student at Kansas State University and had provided a Pap smear. With a court order, police obtained that sample and compared the DNA to the profile from the preserved evidence. The match was definitive.

"I'll never forget the lieutenant called me and said, 'Got the DNA back, it's him.' BTK is Dennis Rader."

With the DNA match in hand, detectives moved in. On February 25, 2005, officers arrested Dennis Rader as he drove home for lunch. He was stunned; the world he had hidden behind—a suburban life, religious leadership, and public respectability—cracked in an instant. In his pockets, investigators placed tangible evidence: the purple floppy disk in a Ziploc bag, the very object he had used to taunt law enforcement decades after his spree began.

Why the Floppy Disk Failed Him

BTK believed he was technologically safe because he used an inherently traceable medium—however old-fashioned—without understanding metadata. The disk contained remnants of computer settings and file registration that directly tied it to a name and institution. The arrogance that drove him to return to the public sphere, and to demand recognition in the face of police, became the mechanism of his undoing. The lesson is straightforward: communication leaves traces, and even the most careful manipulator can overlook the technical details that reveal identity.

Arrest, Confession, and Courtroom Confrontation

Following the arrest, Dennis Rader’s demeanor in court and during interrogation was chillingly calm and matter-of-fact. He explained how he tied and bound, how he strangled, and how he photographed his scenes. For many family members, this was the first time they'd heard an account from the man responsible for so much pain.

"I proceeded to tie her up, put her in a bag overhead and strangled her."

Hearing Rader describe the acts and the positioning of his victims with clinical detail was devastating. Charlie Otero, who had spent decades dreaming of revenge, sat in that courtroom. He told me later that he had planned to assault Rader—"I was going to shank him if I could." But when the moment of confrontation came, life intervened. Charlie received a phone call that his son had been hit by a car and was in a coma. The rage he had carried for thirty years had to coexist with fear for his child. It was a dramatic pivot: all the years he had envisioned violence were overtaken by a deeper need—his son's life.

In court Charlie read a statement on behalf of the Otero family. He made clear the damage Rader had done, not only in taking lives but in forcing relatives to cope with loss across thirty years. He described how his family had been robbed of moments they would never share. Yet Charlie did not simply offer anger. He spoke of transcendence and lessons his parents imparted. The courtroom became the place where victims and survivors publicly reclaimed a voice and demanded accountability.

Sentencing

On June 26, 2005, a jury heard Rader’s confessions and the testimony of those whose lives he had shattered. The court sentenced Dennis L. Rader to multiple consecutive life terms—one for each count. For Wichita and for survivors, the sentence represented the definitive conclusion, at least legally, of a terrifying era.

Aftermath: Redemption, Recovery, and the Long Road Forward

What happens after the arrest of a serial killer? The press cycles through a frenzy. Headlines explode. Neighbors feel safe. But survivors and victims' families remain tethered to wounds that do not close with a courtroom verdict. For Charlie Otero, the conviction allowed him to lay down revenge like a burden he had carried for 30 years. After the sentencing he left the courtroom a different man: "All need for revenge went away and all I could think about was my son." His son survived. Charlie recovered a part of himself.

Charlie went on to do public speaking, bringing a message of hope, accountability, and redemption. He worked with other survivors, including Steve Ralford. Their shared experience of devastation created a bond—an opportunity to rebuild meaning together.

Healing Is Not Linear

Healing is messy and uneven. Some survivors rebuild while others continue to struggle. The legacy of BTK included those who felt severed from life itself, thinking sometimes they wished they had died instead of surviving the horror. The legal resolution cannot resurrect the dead, but it can remove the presence of threat, give closure in some measure, and provide a sense of safety for the living.

For Wichita, the case remains a touchstone for victims’ advocacy and for forensic innovation. For police departments everywhere, the case is a reminder that cold cases may one day be reopened by new technologies and by the missteps of perpetrators. For the public, the BTK saga offers a sober lesson about the complexity of evil—and the ways in which it often hides in plain sight.

Why This Case Matters: Lessons for Law Enforcement and the Public

The BTK investigation is a study in both the strengths and the vulnerabilities of policing and forensic science. A few of the lessons that emerge:

- Preserve evidence—even small things: The careful preservation of pieces of pillowcases or swatches from 1974 made a DNA match possible decades later. Crime scene technicians who document and save material can change the course of an investigation years from the crime date.

- Understanding offender behavior: BTK’s communications show a perpetrator who craved recognition. That ego became his undoing. Investigators who understand what motivates a serial offender can use that psychology—carefully and ethically—to elicit mistakes.

- Technology matters: The floppy disk was a relic, but it carried metadata that exposed Rader. Forensic examiners must remain vigilant not just for content but for digital footprints. Likewise, surveillance footage—though imperfect—provided critical corroboration.

- The importance of public messaging: Law enforcement’s decision to publicize information was tactical; the releases were not simply for the public but were also intended to keep BTK engaged. That outreach, combined with forensics, led to the eventual break.

- Ethical and legal considerations: The use of a relative’s DNA sample under court order raises questions about privacy and methods. Investigators must balance rights against the imperative to protect communities from ongoing threats.

The Psychology of BTK: Control, Ritual, and Recognition

To understand why Dennis Rader did what he did, we can look at the signs of ritual and control in his crimes. BTK—"Bind them, Torture them, Kill them"—boasted of a method. He selected binding as part of the act, used specific knots, and staged scenes for himself—sometimes watching victims like Joey Jr. in the Otero home. He took photographs. He kept souvenirs. He wrote letters. These behaviors are not random. They are typical of offenders who enact crime as performance, who derive gratification both from the act and the aftermath.

Criminal psychologists would emphasize how dangerous this is: a perpetrator who ritualizes acts is often confident in his control, seeks repetition, and eventually craves feedback from a public or from authorities. That craving for acknowledgment is what brought Dennis Rader out of silence. His arrogance that he could taunt law enforcement and remain undetected for years ultimately proved fatal to him.

Community Resilience and the Role of Victim Advocacy

The BTK saga also underscores the importance of community networks and advocacy groups. Families needed legal help, counseling, and support to recover. Survivors like Charlie and Steve found mutual aid in one another. The city leaned on faith communities, social services, and local leaders to process grief. In the longer term, advocacy for victims of violent crime improved because of attention to cases like this: victim impact statements, support services, and trauma-informed care became increasingly part of the justice system’s responsibility.

Media, Myth, and Memory

BTK captured the attention of media for decades. His letters and cryptic communications were perfect for headlines, and the public's appetite for true crime made the story a cultural touchpoint. But media attention has its double edge. On the one hand, coverage can lead to tips and exposure; on the other, sensationalism can distort the human cost and sometimes glorify the perpetrator. In my retelling, I have tried to avoid that trap by keeping the focus squarely on victims, on survivors, and on the work that led to accountability.

The myth-making aspect of BTK's name—transforming private crimes into public legend—allowed Rader to occupy a space he never deserved. Naming him BTK amplified his power. The investigative strategy to invite communication was, in part, an attempt to reclaim that space, to turn the spotlight in a way that forced him into a mistake rather than emboldening him.

After Rader: How Communities Remember

Many communities institutionalize memory. In Wichita, memorials, anniversaries, and education about victim rights became part of the city’s response. Survivors' stories—like Charlie’s public speaking about redemption and resilience—offer living memorials. They humanize the abstract statistics and remind us that justice is more than punishment; it is also repair, recognition, and transformation.

Conclusion: A Long Arc from Horror to Accountability

The story of BTK and the Otero family is horror and hope threaded together. It is horror in the way human beings can harm other human beings with calculated cruelty. It is hope in how communities, technology, and relentless investigative work can eventually yield truth and accountability. Dennis Rader's dreadful acts were facilitated by years of silence, but they ended because he returned to seek notoriety—and his vanity left a trace. The floppy disk, so seemingly archaic, contained metadata that modern forensics could read. DNA that seemed forever out of reach became central because crime scene technicians preserved evidence when many would not have imagined its use decades later.

For Charlie Otero, the case carried consequences that stretched over a lifetime. He survived one of the most traumatic events imaginable. He lost family and nearly lost himself. When Rader was brought to justice, Charlie found the space to choose a different path—toward living in the memory of those he lost and in the life of his son. His testimony in court, his public speaking, and his relationship with other survivors reflect a profound and difficult form of healing that honours the memory of those who can't speak for themselves.

This account does not close the wound. The pain remains. But the arc of justice shows that persistence, scientific advancement, and a community's refusal to forget can eventually reveal truth. That truth matters—in memory, in court, and in the work of rebuilding lives.

If you want to understand more about the case, the individuals involved, and how forensic science transformed cold cases into solvable investigations, I encourage you to explore the resources available through victims' advocacy groups and forensic science literature. Above all, remember the people at the center of this story: Joseph and Julia Otero, Joey Jr., Josephine, Catherine Bright, Shirley Vian, and the many survivors who lived with the consequences for decades.

Resources and Recommended Reading

- Victim Impact Statement compilations and survivors’ testimonies (local and national archives)

- Forensic science textbooks on DNA technology and cold case investigation

- Academic works on criminal psychology, specifically ritualistic offenders and offender ego dynamics

- Local Wichita newspapers' archives for original reporting and trial coverage

To the families and survivors who shared their stories: thank you for your courage. To investigators who never gave up: your persistence matters. And to readers: when violence shatters lives, justice can be delayed but not necessarily denied. This story is painful, but it is also a testament to what can happen when communities insist on truth and refuse to forget.

0 Comments