I want to tell you a story that reads like the darkest imagination of a Hollywood horror writer, except every detail in this account is painfully real. It begins in a quiet Chicago suburb, moves through a trail of disappearances and a survivor's desperate sleuthing, and ends in a discovery that forced an entire community to confront an unspeakable truth: a graveyard hidden beneath an ordinary house owned by a man who entertained children as a clown.

Table of Contents

- Summary of what happened

- Why this story matters

- Setting the scene: Chicago in the 1970s

- The first disappearance that later mattered: Johnny Bukovic

- The turning point: Jeffrey Rignall's attack and the art of survivor-investigation

- Gacy's public life: the mask he wore

- Why early suspicion failed

- Robert Peast: the missing 15-year-old who reopened the investigation

- Searches, small pieces of evidence, and the trap door discovery

- Gacy’s arrogance and the second warrant

- Discovery of the crawl space graveyard

- The arrest, confession, and chilling nonchalance

- Bodies recovered from property and river

- The trial: guilt, insanity defense, and the jury's decision

- Conviction, sentence, and execution

- The cultural aftermath: clowns as icons of fear

- Lessons investigators and communities learned

- The human cost

- Frequently asked questions

- Final reflections

Summary of what happened

Between the mid 1970s and 1978 a number of young men vanished from the streets of Chicago and surrounding suburbs. The disappearances—initially dismissed as runaways or the natural churn of a mobile, hitchhiking-era population—began to form a pattern only when a survivor identified his attacker and a persistent detective followed up on a missing 15-year-old named Robert.

The man they uncovered was John Wayne Gacy, a respected local businessman who cultivated a public persona as a civic-minded contractor, a political organizer, and, incongruously, as Pogo the Clown, a volunteer at children's parties and hospitals. Behind that public face Gacy maintained a secret life of sexual violence, strangulation, and burial of victims in a crawl space beneath his Norwood Park home. Ultimately investigators uncovered dozens of bodies in his property and the Des Plaines River. Gacy was convicted and sentenced to death.

Why this story matters

What makes this case uniquely chilling is the contrast between the ordinary and the monstrous. It forces us to ask how someone so embedded in community life could also be committing the most extreme violence. The case also illustrates investigative realities of the 1970s: a pre-internet world with limited inter-departmental communication, fewer forensic tools, and cultural stigmas that impeded victims from being taken seriously.

But this is not simply an exercise in horror. The Gacy case also reveals how determined victims, methodical detectives, and small pieces of mundane evidence—like a film-developing receipt—can combine to unravel a supposedly impenetrable lie.

Setting the scene: Chicago in the 1970s

The mid 1970s were a very different time. Hitchhiking was routine. Young men drifted across neighborhoods and states in search of work, rides, or a place to stay. A missing person might be gone for days or weeks without raising alarms. That context mattered deeply in the early stages of the Gacy investigation.

Predators who target vulnerable people look for victims who will not be sought immediately or whose absence will be explained away. In an era without easy electronic records or nationwide databases, the pieces of a serial pattern could be scattered across precinct lines and never connected. In that environment John Wayne Gacy found opportunity and cover.

Hitchhiking, marginalization, and victim selection

Offenders typically choose victims who are accessible and unlikely to be quickly missed. That pattern explains why many of the missing in Chicago in this period were young men who lived transient lives, were estranged from family, or were engaged in sex work. They were high-risk targets because even when they were noticed missing by some, the official response often labeled them runaways.

Gacy, as it would become clear, preferred boys and young men who were vulnerable and unlikely to prompt immediate, rigorous police inquiries.

The first disappearance that later mattered: Johnny Bukovic

In the summer of 1975 18-year-old Johnny Bukovic went to the residential office of PDM Contractors, where he worked. He had gone to confront an employer about wages he believed were owed to him. Witnesses described an angry conversation. Johnny threatened to expose the boss's sketchy accounting. He left the site with friends—but then he vanished.

The following morning Johnny's father found the teenager's car a few blocks from home with the key in the ignition. Checkbook in the glove box, wallet full of cash in the center console. It did not look like a young man who ran away.

Police took a report. They asked questions. They spoke briefly with the contractor, who said Johnny had left with friends. Because of the lack of direct proof and the contractor's status in the community, the disappearance was never solved. That early brush with Johnny's employer would resurface years later.

The turning point: Jeffrey Rignall's attack and the art of survivor-investigation

Three years after Johnny vanished another story changed everything. On a night in 1978, 26-year-old Jeffrey Rignall was walking home when a black Oldsmobile pulled up. The driver invited him to get high. Rignall entered the car. What followed was a prolonged nightmare.

He pounces, shoving a rag over his nose and mouth. It's soaked with a sweet-smelling liquid, probably chloroform. He wakes several times during the ride... Then the kidnapper puts the rag back over his mouth, and everything goes black.

Rignall regained consciousness in a house he'd never seen before. He had been stripped, restrained, raped, beaten, and tortured for hours. The attacker would render him unconscious again and resume the assault. After many hours the assailant dumped Rignall, unconscious, in a park. Rignall informed the police and gave a description that was disturbingly thin: a white man with a mustache and a black Oldsmobile. That was not much to go on.

Faced with indifference and the constraints of police resources at the time, Rignall took matters into his own hands. He returned to the expressway exit he had seen while drifting in and out of consciousness and staged a stakeout. Against the long odds, against thousands of cars, Rignall spotted the same black Oldsmobile heading into the suburbs. He tailed it to Norwood Park and followed it to 8213 Somerdale Avenue.

Rignall recorded the license plate and the address, then took that information to the police. This was the moment the case moved from an anonymous assault into a criminal investigation with a person of interest: John Wayne Gacy.

Why Rignall's stakeout mattered

Survivor testimony is often dismissed, smeared, or weakened by forensic limits. But Rignall's persistence provided something detectives sorely needed: a lead that directly tied the assault to a physical address. It changed the investigation from abstract to concrete.

Rignall should be remembered in any retelling of this case not only as a survivor but as a relentless investigator who refused to let the system ignore him.

Gacy's public life: the mask he wore

John Wayne Gacy was not a typical suspect. He was a well-known local businessman and trusted member of civic organizations. He worked as a contractor, ran a successful small business, and built a seemingly respectable family life in a white-picket neighborhood just a short drive from O'Hare Airport.

Gacy took great pains to craft a public image that would disarm suspicion. He volunteered for community events, was active in local politics, and cultivated relationships with neighbors and civic leaders. He was photographed in public events, and his friendly face helped shield him from scrutiny.

Pogo the Clown

Where Gacy's reputation veered into the bizarre was his extracurricular activity as Pogo the Clown. He joined the Jolly Joker Clown Club and performed at children's parties, painted his face, and entertained kids in hospitals. He even created his own costume and stage persona.

He said, "I'm a professional clown on weekends for charities, kids' parties. Pogo the clown!"

The clown persona gave him an additional layer of plausible deniability. Who would think that a man who appeared at birthday parties could also be a predator? Gacy later said—brazenly and chillingly—that "a clown can get away with murder." That line captured the audacity behind his double life.

Why early suspicion failed

When Johnny Bukovic disappeared years earlier, police interviewed Gacy because Johnny had visited the contractor's office before he vanished. Gacy's clean reputation, the absence of conclusive evidence, and the social dynamics of the time led investigators to dismiss him as a suspect. That failure illustrated two vulnerabilities in law enforcement of the era: the tendency to accept outward respectability as exculpatory and the technical limits of evidence collection and interagency communication.

Gacy’s later misbehavior and Rignall’s identification began to crack that cover—but evidence still mattered, and much of it is mundane. Detectives needed a smoking gun that tied a missing teenager concretely to Gacy’s home.

Robert Peast: the missing 15-year-old who reopened the investigation

In the summer after Jeffrey Rignall's attack, the case took another dramatic turn. Elizabeth Peast came into a Des Plaines police station terrified and pleading for help: her 15-year-old son Robert had not returned from work. Unlike many of the earlier missing, Robert was not a drifter or an anonymous young man; he was a model kid, well-known to his family, and unlikely to run away.

On the evening he vanished Robert had been working at a pharmacy. His mother, waiting to drive him home on her birthday, remembered he had run off to meet someone about a potential job. The boy never returned.

Robert's boss identified the man Robert had gone to meet as a contractor named John Gacy. When Lieutenant Joe Kozenzak of Des Plaines PD followed up on that name he found a troubling criminal history: a prior conviction in Iowa for sodomy of a 15-year-old and a pending battery case based on Jeffrey Rignall's allegations.

Why Robert's case was treated differently

Detectives viewed Robert's disappearance with urgency because he was deeply tied to his family. Cases like his—where parents could identify and account for short absences—create a higher probability that something violent occurred. Kozenzak understood the crucial importance of time: the first 48 hours often determine what evidence remains recoverable.

Searches, small pieces of evidence, and the trap door discovery

Kozenzak's team visited Gacy's Somerdale Avenue home. Their goal was to find Robert—alive if possible—or at least to establish that Robert had been inside Gacy's residence. Gacy was cooperative on the surface. He attempted to explain away inquiries by offering stories about a deceased uncle and asking to speak with his mother. But detectives noticed behaviors that made them suspicious and kept pushing.

As officers searched the home they found an assortment of items that painted a picture inconsistent with Gacy's public image: gay pornographic videos and magazines, sex toys, handcuffs, a board modified to restrain human hands and feet, and the kinds of personal effects that hinted at victims who did not belong to Gacy—a class ring marked JAS, underwear too small for an adult of Gacy's size, and a blue hooded coat similar to the one Robert had been wearing.

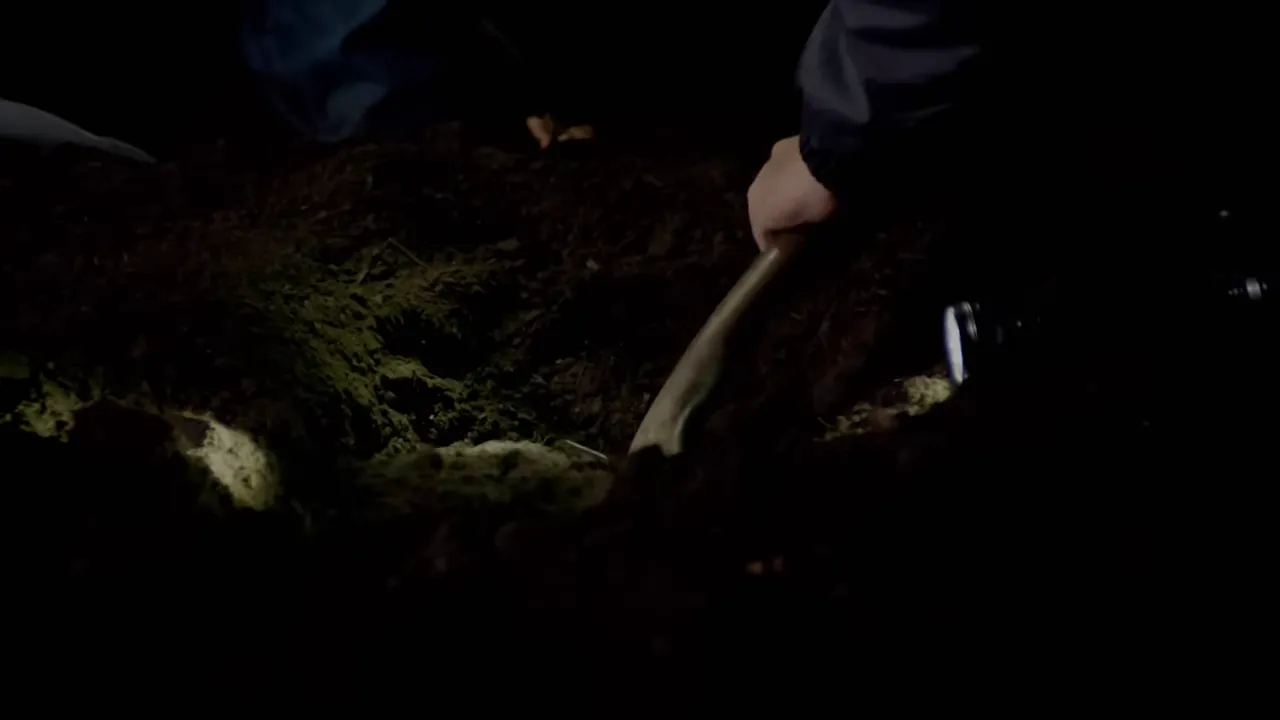

Then an officer noticed a trap door in a closet: a hidden access point to a crawl space under the house.

Kozenzak reached down, lifted the trap door, and inhaled an odor that would help break the case: a strangely sweet, putrid smell rising from the vents. The smell was unmistakable to an experienced investigator. It was the scent of death.

It smells like a morgue.

That odor, combined with the pharmacy film-developing receipt found in Gacy’s trash and the array of suspicious personal items, supplied the probable cause needed for a second, full search warrant.

The film-developing receipt: a small but decisive link

Evidence is rarely dramatic. Most often it is ordinary: a receipt, a phone number, a timestamp. In this case, the receipt from Nissan Pharmacy was the smoking gun that placed Robert in Gacy’s house. Robert’s mother later recalled that a coworker had slipped a film-developing receipt into the pocket of Robert's blue coat the night he disappeared. Detectives found an identical receipt in Gacy's kitchen trash. They confirmed the matching numbers with the pharmacy. That match proved beyond reasonable doubt that Robert had entered Gacy's home.

Gacy’s arrogance and the second warrant

Gacy’s behavior after the initial search revealed something that would ultimately aid investigators: he became increasingly cocky. He invited officers back into his house. He bragged about his clown persona and actually quipped that clowns could "get away with murder." That combination of arrogance and a false sense of control made him more vulnerable; he underestimated the attention of surveillance and overlooked the ways in which minute evidence could be pieced together.

At one point, Gacy drove recklessly, attempted to manipulate strangers, and behaved as if the law had no real power over him. A simple drug offense ultimately provided the arrest opportunity police needed to take him into custody and execute a more thorough search backed by evidence technicians.

Discovery of the crawl space graveyard

With Gacy in custody and a court-approved warrant in hand, detectives returned to 8213 Somerdale Avenue and opened the trap door under the house. What they found beneath the floorboards would become one of the most horrifying crime scene discoveries in modern American history.

The hard-packed dirt under the house was not undisturbed. Investigators began to dig. Almost immediately they found human bones. One body led to another. The crawl space was filled with bodies—two dozen and more—laid side by side in the dim subterranean tomb Gacy had maintained under his house. In total police recovered 26 bodies in the crawl space and later another hidden beneath the garage concrete. Across the Des Plaines River additional victims were recovered where Gacy admitted he had been dumping bodies after he ran out of room under his house.

For investigators the scene was more than a catalogue of gore. It was a psychological blow. The act of sifting through the remains, moving the bodies, and assembling a record of names and identities is brutal work that leaves deep scars on those who must do it. Detectives later spoke about the challenge of remaining detached while handling human remains that had been hidden under a home for months or years.

Why Gacy buried victims where he did

Gacy's mind was driven by a desire for control. Burying victims under his own house allowed him to maintain possession of them even in death. It is a perverse logic: to hold onto that power even after life. He later admitted to disposing of additional victims in the Des Plaines River when he ran out of space. For him the bodies were objects—tools he used to satisfy his urges and then discarded.

The arrest, confession, and chilling nonchalance

When detectives confronted Gacy with the bodies they had found, his reaction was devoid of the remorse most people would expect. He explained strangulation methods calmly and treated the conversation almost clinically, as if instructing others on technique. That detachment is one of the classic hallmarks of psychopathy: a lack of empathy and remorselessness about actions that would horrify most human beings.

He said, "I showed him the rope trick." You do a little double loop... If it feels good to Gacy, that's all that matters.

Gacy admitted to strangling Robert Peast and to disposing of his body off a bridge when there was "no room under the house." He spoke about the victims as objects, and when arrested he even maintained a level of bluster. As officers read him his rights, he showed no apparent remorse. When he was later taken to the penitentiary and ultimately to the death chamber, he continued to exhibit contempt, telling authorities to "kiss my ass" as lethal drugs were administered.

Bodies recovered from property and river

Police recovered 27 bodies from Gacy: 26 in the crawl space and one more beneath the garage floor. In the months that followed, teams scoured the Des Plaines River and pulled out additional remains. Some victims were identified by family and friends; others could only be matched through circumstantial and forensic evidence.

One particularly cruel irony was that Robert Peast's remains were found in a section of river he and his father used to canoe. The recovery provided a measure of closure for grieving families who had endured months of uncertainty.

The trial: guilt, insanity defense, and the jury's decision

Gacy's trial began after an exhaustive investigation and weeks of testimony from more than a hundred witnesses. The central legal question was not whether he had killed the victims; he ultimately admitted to the killings. The pivotal issue presented to jurors was whether he was legally insane at the time he committed the murders.

Defense attorneys argued insanity. The prosecution countered by pointing to the methodical, patterned nature of the murders, arguing that consistent tactics and calculated behavior looked like the work of a meticulous, clever offender rather than someone lacking reason. The jury deliberated for a short time and returned a verdict of guilty on 33 counts of first-degree murder.

Why the insanity plea failed

Insanity as a legal defense requires proof that the defendant, because of mental disease or defect, did not understand the wrongfulness of his actions or could not conform his conduct to the law. The prosecution presented a pattern of deliberate steps, planning, and care that suggested Gacy understood his actions and took measures to conceal them. Those calculated decisions undermined claims that he was irrational in a legally meaningful way.

Conviction, sentence, and execution

Gacy was convicted and sentenced to death. After years on death row, the sentence was carried out. Even in his final moments he projected defiance, a continued attempt to retain control. When authorities administered the lethal injection Gacy's final words and demeanor reflected the same arrogance and contempt that marked much of his adult life.

The cultural aftermath: clowns as icons of fear

Gacy's identity as Pogo the Clown leapt into the cultural imagination. A figure that had traditionally symbolized innocence, silliness, and childhood happiness became a totem of terror. From horror movies to Halloween stores, the "evil clown" trope proliferated, and Gacy's crimes played a direct role in shaping that iconography.

There is a complex ethical question here: should a horrific crime that involves a performer of children's entertainment change the way society views an entire profession? The answer lies in nuance: most clowns are harmless, kind entertainers. But Gacy's appropriation of clown imagery as a facet of his public mask left an indelible scar on popular culture.

Lessons investigators and communities learned

The Gacy case forced police departments to rethink how they communicate across precincts and how they treat reports of missing young men. A few of the key takeaways include:

- Persistence matters. The story demonstrates how survivors and family members who refuse to accept easy explanations can drive investigations forward.

- Ordinary objects can be decisive. A film-developing receipt in a trash can was the piece that tied a missing teen to the house. Don’t underestimate mundane evidence.

- Public persona is not proof of innocence. A respected community member can still be a predator. Outward respectability is not dispositive.

- Communication between jurisdictions is vital. In a pre-digital era the inability to link missing-person cases allowed serial predation to continue.

- Trauma-informed policing is necessary. Victims and families who openly discussed sexuality or vulnerability were sometimes stigmatized, which delayed effective responses.

The human cost

Beyond the headlines and court records the most important part of this story is the human cost. Families lost sons, brothers, and fathers. Survivors of assault lived with wounds that weren’t only physical. Investigators who uncovered the crawl-space graves carried the psychological weight of what they had seen for the rest of their lives.

We must remember the victims not as statistics but as people with names, families, and futures. In discussing the case it is our responsibility to honor those lives and to recognize the ongoing impact of such violence on communities.

Frequently asked questions

How many victims did John Wayne Gacy kill?

Officially investigators recovered 33 victims who were linked to John Wayne Gacy: 26 bodies found in the crawl space under his home, one hidden beneath the concrete of his garage, and additional remains recovered from the Des Plaines River. Gacy ultimately faced charges and convictions totaling 33 counts of first-degree murder.

Why was Gacy not caught sooner despite multiple disappearances?

Several factors delayed detection: the cultural norms of the 1970s made hitchhiking and transient living common, so many missing-person cases were labeled runaways; law enforcement databases and inter-precinct communication were limited; Gacy cultivated a respectable public persona that made suspicion less likely; and earlier allegations—when they did surface—were not easily corroborated with physical evidence until key items like the pharmacy receipt were discovered.

What role did Jeffrey Rignall play in catching Gacy?

Jeffrey Rignall was a survivor of a brutal attack and later identified the assailant's vehicle. Frustrated by slow investigative momentum, Rignall personally staked out the expressway exit he remembered and eventually followed the suspect's car to Gacy's house. His actions provided a license plate and an address that helped police link the attack to John Wayne Gacy.

Why did Gacy bury victims in his crawl space?

Gacy's actions reflected a desire for control and possession. Burying victims under his house allowed him to keep them literally within his domain. When he ran out of space, he disposed of other victims in the Des Plaines River. For Gacy the bodies were objects related to gratification and then discarded, demonstrating a profound lack of empathy and regard for human life.

Was Gacy found legally insane at his trial?

No. While Gacy admitted to the killings and there was discussion of mental illness, the jury found him guilty on all counts of first-degree murder. The prosecution argued that the methodical and consistent pattern of the killings indicated calculated, deliberate behavior rather than a lack of understanding of wrongfulness, and the jury accepted that reasoning.

What lasting impacts did the case have on popular culture?

Gacy's role as Pogo the Clown transformed public perceptions of clowns and contributed to the "evil clown" trope in movies, books, and Halloween imagery. The case also spurred conversations about how outwardly pleasant figures can harbor violent secrets and about the need for better protections for vulnerable populations.

Final reflections

This case remains one of the most disturbing examples of how evil can hide behind a friendly face. John Wayne Gacy's crimes were an extreme combination of predation, manipulation, and brutality. Behind a respectable business front and a painted smile he cultivated opportunities to lure, torture, and kill young men.

Yet the story also shows human agency in the face of failure: a survivor who refused to let the system ignore him, a detective who would not relent until a trap door and a receipt were followed to their inevitable conclusion, and families who demanded answers. Those efforts are what brought Gacy to account.

Remembering the victims, studying the investigative lessons, and honoring the work of those who refused to accept easy answers are the best ways to ensure that the lessons of this horrific case remain with us. Cases like this teach law enforcement, communities, and individuals how to be persistent, how to value ordinary evidence, and how to refuse the comfortable temptation of assuming that public respectability equals goodness.

When we look back at Gacy's crimes we must hold three truths in mind. First, monsters sometimes wear ordinary faces. Second, the smallest piece of evidence can break the most carefully constructed lie. Third, persistent people—survivors, detectives, and loved ones—can change the course of an investigation and force the truth into the light.

0 Comments