, I explore one of the most shocking criminal discoveries in American history: the grotesque revelations unearthed in a small farmhouse outside Plainfield, Wisconsin, in November 1957. What began as a routine missing-person investigation quickly exploded into a national nightmare. It revealed not only the murder of two local women, Bernice Warden and Mary Hogan, but also a macabre collection of human remains and artifacts so chilling they would reverberate through popular culture for decades.

This article recounts the life, crimes, investigation, psychological portrait, trial, and cultural legacy of Edward "Ed" Gein. It draws on the eyewitness accounts, police reports, and psychiatric evaluations that transformed Plainfield into the unlikely epicenter of American horror. If you watched the Documentary Vault video, this companion piece expands on the themes and details presented there—providing context, analysis, and a clear timeline so readers who never saw the footage can understand exactly why this case became so infamous.

Outline & What You’ll Read

- Introduction and the discovery that shocked America

- Early life and family background of Ed Gein

- Isolation, grief, and the unsettling spiral after the deaths of family members

- The crimes: murder, grave robbing, and the farmhouse discoveries

- Investigation, arrest, interrogation and confessions

- Legal proceedings, psychiatric evaluations, and institutionalization

- Aftermath: Plainfield’s reaction, the destruction of the house, and the marketplace for relics

- Cultural legacy: From Psycho to The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and beyond

- Psychological analysis and the difficult question of "evil"

- Conclusion and reflections on why this case still haunts us

The Discovery: A Small Town’s Nightmare

It was November 16, 1957—the first day of deer hunting season—and the men of Plainfield, Wisconsin, had mostly gone into the woods. That detail matters. In a town where nearly everyone knows everyone else, timing shaped events. The disappearance of 58-year-old Bernice (often called Bernie) Warden, owner of the Warden Hardware Store, might have been noticed more quickly at other times. On this day, while many men were in the field, Bernie was missed only hours later.

When law enforcement finally converged on Ed Gein’s property—after a receipt for antifreeze in Gein’s name and eyewitness suspicion linked him to Bernie—the search of his outbuildings produced a sight that broke the bounds of ordinary crime scenes. One officer turned on his flashlight and "beamed it around and saw this object that was hanging from the rafters." At first it looked like a gutted deer; then the full horror revealed itself: a woman's corpse hung by its heels, slit from sternum to pelvis, gutted like game.

The farmhouse itself, when officers finally entered, was worse than anyone imagined. They found human bones, skulls fashioned into bowls, a lampshade made of human skin, twelve human heads, gloves made from skin, jars of body parts, a box containing female organs, and a belt fashioned of nipples—items catalogued in police reports and described in breathless national headlines.

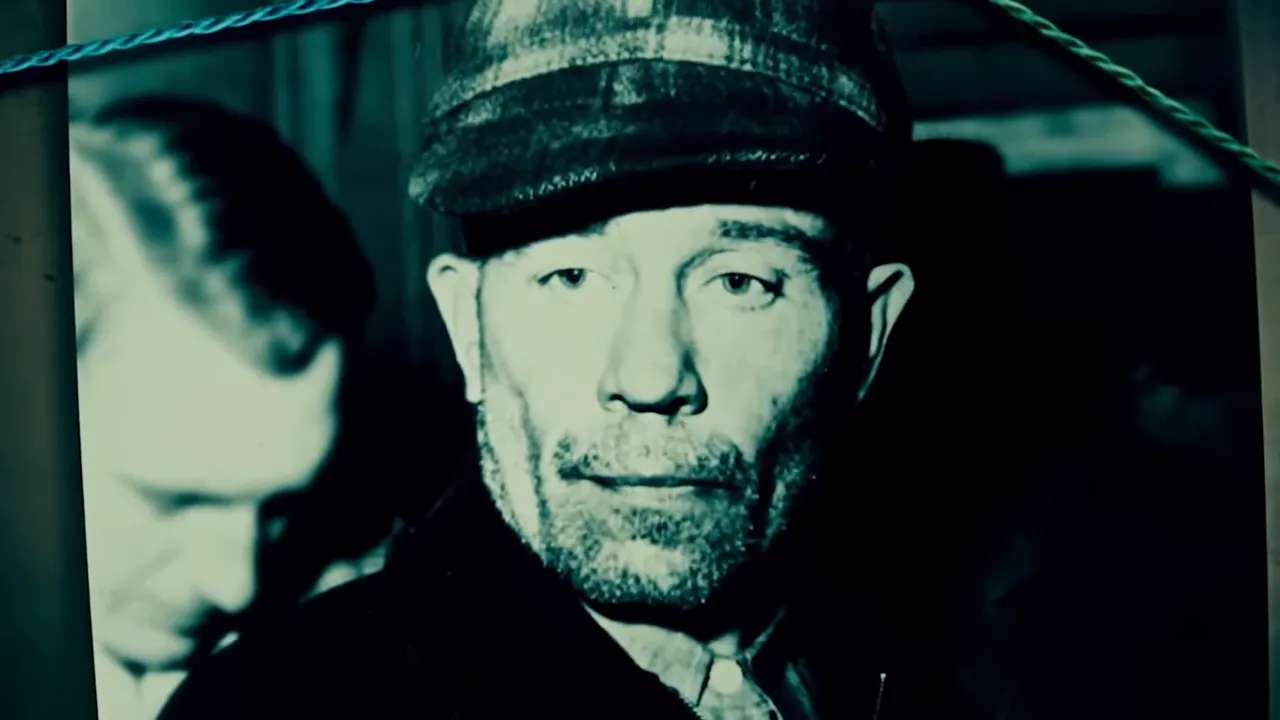

Who Was Edward Gein? A Life Built on Isolation

Understanding Ed Gein’s crimes requires tracing his life back to a farmhouse on a 150-acre plot at the corner of Archer and Second Avenue near Plainfield. Born August 27, 1906, in La Crosse County, Wisconsin, Edward Gein moved to Plainfield with his family at age eight. His parents—Augusta (the matriarch) and George—were an unhappy mix: Augusta a domineering, devout woman with extreme views about sin and women, and George an alcoholic who functioned mostly under her thumb.

Augusta's theology and rigid moral code defined household life. She called the outside world a place of vice—La Crosse, by her estimation, was a "Sodom and Gomorrah"-type threat to her children. She demanded that her sons not associate with the outside world, especially the town’s women. This created an intensely insular childhood for Ed and his older brother Henry, where friends were discouraged and any outside contact was suspect.

As a result, Ed grew up in social isolation: a loner who dropped out of school between the ages of 12 and 13 to work the farm. He was described by neighbors as quiet and meek, someone who would say hello and always had time for a joke—someone ordinary in the street, unreadable in the mind. Yet that surface normalcy hid a childhood defined by fear, shame, and deprivation.

Family Tragedy and the Shifting Household

Ed’s father, George, died of heart failure on April 1, 1940. With George gone, Augusta’s control over the household intensified—but Henry, Ed’s older brother, began to emotionally and psychologically separate from their mother. Henry occasionally criticized Augusta's suffocating hold; that small act of independence appears to have seeded resentment in Ed, who worshipped Augusta and regarded her almost as an infallible deity.

In May 1944, Henry died under circumstances that would later be reinterpreted through a darker lens. While fighting a brush fire, Henry vanished from the group extinguishing it; Ed returned to fetch help and led responders to Henry’s body. The medical examiner concluded Henry died of a heart attack and struck his head as he fell. Yet later, after Gein’s crimes were exposed, people whispered that those mysterious bruises suggested foul play—that perhaps Ed had murdered Henry because of his insubordination toward Augusta.

Henry’s death devastated Augusta and led to a stroke. She lingered, partially incapacitated, for 19 months—nursed by Ed, who apparently took on an almost infantile role around her, sometimes sleeping beside her and tending to her. When Augusta died on December 29, 1945, the extent of Ed’s dependence on his mother became brutally clear. At the funeral, Ed, then in his late thirties, was observed wailing like a child—an emotional immaturity that would become a theme in psychiatric reports. With both male adults removed and Augusta gone, the house, and Ed’s psyche, began to unravel.

From Grief to Obsession: The Emergence of a Dark Fantasy

Grief, profound loneliness, and an isolationist upbringing created a fertile ground for obsession. Ed retreated deeper into solitude. He read extensively: medical textbooks, pornographic magazines, and lurid stories about wartime atrocities—he reportedly took a particular interest in Ilse Koch, a figure infamous for collecting patches of human skin in Nazi concentration camps. These readings, combined with Ed’s practical knowledge of carcass preparation from farm life and the community’s hunting culture, produced a chilling convergence of fantasy and skill.

By 1947—two years after Augusta’s death—Ed had begun visiting local cemeteries at night. He would read obituaries in local papers and seek out women whose age and appearance reminded him, in some vague way, of his mother. On nights when graves had been recently filled and the soil still loose, Ed dug up corpses and removed body parts. Sometimes he took whole bodies back to the farmhouse; other times he returned with only portions. He fashioned grotesque artifacts from the remains: masks, upholstery, clothing, and household objects made from human skin and bone.

The Psychology of Grave Robbing

Why grave robbing? For Ed, exhumation was both a desperate attempt to reconstitute his mother and a compulsion born of an eroding sense of reality. The acts blur into contradictory impulses: on one hand, a childlike yearning to return his mother to life; on the other, a rage and perverse domination over female bodies. He took body parts that could be used to recreate a feminine presence—masks, skin apparel, or a "skin suit"—and then used them to perform rituals in which he embodied that woman.

According to his later confessions, Ed crafted a "skull-cup" soup bowl, used skulls as decorative vessels, and even admitted to donning a skin suit made from a female torso and leggings, wearing a flayed-face mask, and wandering his property pretending to be his mother. The ghastly combination of maternal worship and mutilation marks a pathology both primitive and bizarre—a ritualistic attempt to collapse the boundary between the dead and the living.

The Murders: Mary Hogan and Bernice Warden

Up until 1957, Gein’s crimes had largely involved grave robbing and the theft of body parts. But the darkness escalated to homicide. On December 8, 1954, Mary Hogan—a tavern keeper who ran a roadside bar outside Plainfield and an 18-and-up hangout for local teens—disappeared. Gein reportedly told residents, "She's not missing. She's up at the house," words dismissed as the ramblings of an odd man. It would be nearly three years before investigators would unearth Mary Hogan’s fate: her severed head was discovered in a paper bag in Gein’s home during the 1957 search.

The killing that exposed everything happened on November 16, 1957. Ed walked into Warden Hardware and asked to buy a half-gallon of antifreeze. Bernice Warden served him, wrote a receipt, and later turned her back to show him a rifle in the store window. When she did, Ed shot her in the back of the head, loaded her body into his truck, and drove back to his farm. The timing of deer season explains why Bernie wasn’t immediately missed: many of the town's men were away hunting. Her son, returning to the store later, found blood across the floor and immediately suspected Ed due to the recent attention Ed had shown his mother.

That day, in the dark and cold of a Wisconsin November night, officers entered the Gein property and first found Bernice's butchered corpse hanging in the summer kitchen. Once inside the house the scale of atrocity became undeniable: a collection of human remains and objects that read like a catalog of desecration.

The Farmhouse: A Catalog of the Unimaginable

Police inventory lists and witness descriptions from that night reveal items that remain difficult to read without a visceral reaction. Among the discoveries:

- Chairs upholstered in human skin

- A lampshade made of human skin

- Twelve human heads

- Gloves made from the skin of fingers

- Jars containing human noses

- A box filled with female genitalia, some painted and tied with ribbons

- A belt fashioned from female nipples

- A pole adorned with human lips

- Preserved facial masks—flayed faces with lipstick

- A full "skin suit" crafted from a female torso and leg skin

These items were not stolen for profit or trophy; they were components of a private, grotesque ritual. They were intended for an internal world that made sense to Gein—a world where corpses could be rearranged into a living tableau and where the presences of women could be reconstituted, controlled, or punished.

Public Reaction and Shock

The discovery in Plainfield was a cultural rupture. In the context of late-1950s America—often idealized for small-town normalcy and family values—the grotesque artifacts inside an unassuming farmhouse were a nightmare that exposed a dark underside. Residents who had known Ed as a quiet, helpful neighbor found themselves reassessing every memory. A local woman said, "When I heard of his arrest, I couldn't believe it. I was sure they had the wrong person because it just didn't seem like anything that they were telling us was the Ed that we all knew." The dissonance between everyday acquaintance and monstrous reality made the case especially unsettling.

Investigation, Arrest, and Interrogation

Law enforcement arrested Ed Gein that day at a neighbor's house, where he had been eating dinner. One team took him into custody while another processed the farmhouse. The grisly finds immediately made national headlines, and investigators treated Gein as a person of enormous interest. Yet the assumption that he was a serial killer was complicated by the pattern of grave robbing. During interrogation, Gein confessed to two murders—Bernice Warden and Mary Hogan—but also to years of grave desecration.

Between 1947 and 1952 Gein told officers he had regularly visited the local cemetery at night, digging up graves whose soil was still loose. He followed obituaries to choose bodies. Investigators exhumed many graves and found coffins broken open and bodies missing, sometimes with only skeletal remains left behind. Gein admitted to desecrating nine graves, though the household inventory suggested more (police had found twelve human heads and body parts from a number of victims), so the full mathematical accounting of victims versus admitted desecrations never fully closed.

Gein’s first words after arrest provided a strange glimpse into his psyche. After roughly 24 hours of arrest, he "started talking" and reportedly asked for "an apple pie with a slice of cheese on it." This childlike request was interpreted by psychiatrists as evidence of emotional and developmental stunting: a man whose affective and social maturity had arrested at a juvenile point.

Legal Outcome and Psychiatric Evaluation

At his arraignment on November 21, 1957, Ed Gein pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity and was judged unfit to stand trial. Medical professionals observed evidence of psychosis—hallucinations, disordered thought, and reports that he heard voices or that the trees "would start talking to him." This clinical picture diverged from the modus operandi of many serial killers, who often understand the nature of their crimes and are not psychotic.

Gein was sent to the Central State Hospital for the criminally insane in Waupun, Wisconsin (often spelled "Warpen" in popular accounts). He spent 11 years institutionalized before being judged competent to stand trial. In 1968 a judge found him guilty of the murder of Bernice Warden but legally insane; rather than being sent to prison he was committed back to a mental hospital for the remainder of his life. That life ended on July 26, 1984, when Gein died of lung cancer at age 77. He was buried in the family plot next to his mother—the same cemetery he had desecrated for so many years.

Life Inside the Institution

Those who evaluated and treated Gein found an odd contradiction. In the hospital he was described as small, meek, and largely nonviolent—someone who "lived there very peacefully" and was not disruptive. Forensic psychiatrist Dr. Helen Morrison and other clinicians reported Gein as quiet and childlike in affect. To them, the monstrous figure portrayed in headlines seemed nearly unrecognizable as the man they observed in structured care. This paradox—an outwardly harmless institutional patient who had committed unspeakable acts—fuels ongoing debates about how to understand extreme offenders.

Plainfield Aftermath: Burning the House and the Marketplace for Morbid Relics

For the people of Plainfield, the scandal left a stain. Residents did not want the house to become a morbid attraction. In 1958 the property was auctioned, and in the days before the sale the house burned to the ground. While some accounts cite accidental causes—local burn piles and wind carrying embers—other accounts whispered of arson motivated by a desire to erase the notorious site. Regardless, the physical structure that had birthed America’s modern bogeyman was gone.

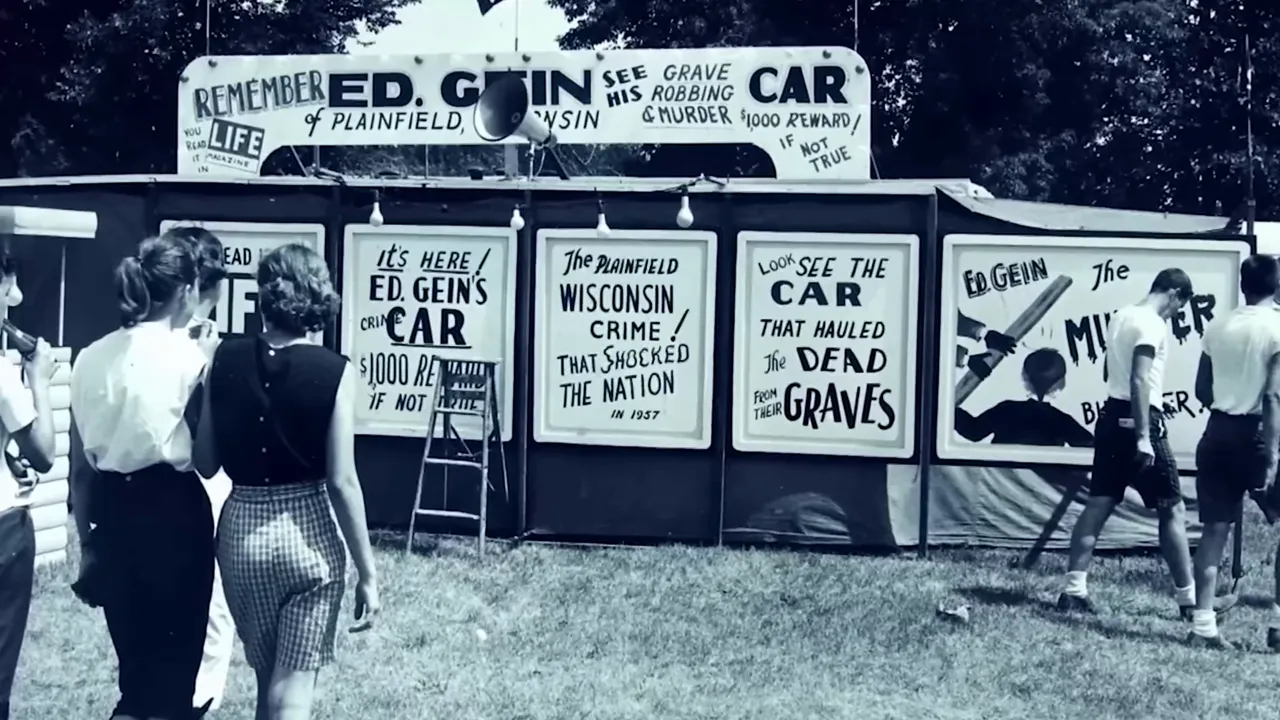

Public fascination did not wane. In March 1958 Gein’s car, used to transport victim bodies, sold at auction to a carnival operator for over $700. The operator charged twenty-five cents for photos beside the vehicle—evidence that "wound culture" and commerce around revulsion were alive even then. "Murderabilia"—the market for collectibles associated with notorious crimes—has persisted and grown since Gein’s era. Items allegedly connected to him, from headstone fragments to postcards, have been bought and sold, fueling ethical debates around the commodification of violence.

Cultural Legacy: How Ed Gein Shaped American Horror

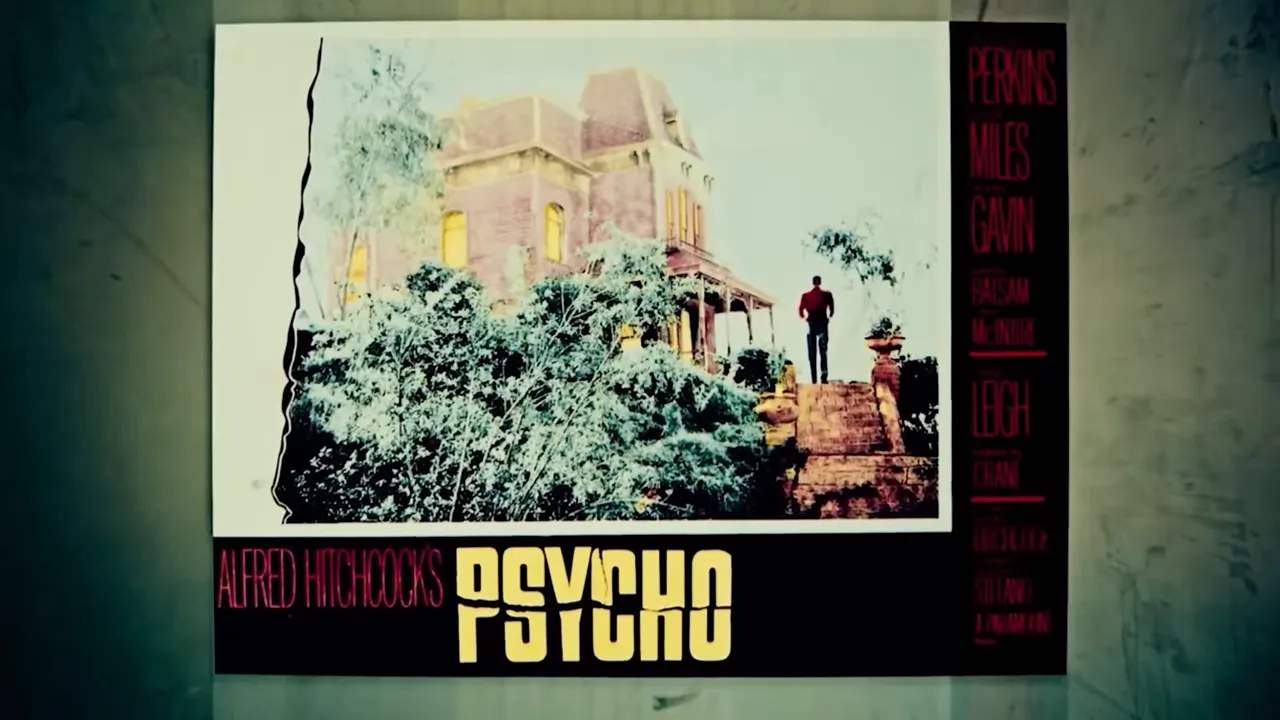

Ed Gein’s case reshaped American popular culture. He directly inspired several landmark works of fiction and film. Robert Bloch, a pulp horror writer living in Wisconsin at the time, used news of Gein’s crimes and psychiatric portrait to construct Norman Bates in his novel Psycho. Alfred Hitchcock’s adaptation made Bates a household name, linking the ordinary-looking motel owner to a monstrous psychosis. The linkage was explicit: Bloch’s novel and subsequent interviews connected Norman Bates to Gein's "mama's boy" pathology.

Director Tobe Hooper drew on Gein for the backstory and phenomenology of Leatherface in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre—an ordinary rural guy who wields a chainsaw, lives in a dilapidated household, and wears masks and skins to blur human identity. Thomas Harris’ Buffalo Bill in The Silence of the Lambs is another descendant: a man who skins and fashions female garments from victims, motivated by the desire to become somebody else. Across these works, Gein’s influence is unmistakable: he helped move horror from castles, monsters, and the supernatural toward a new, American terror—the serial killer next door.

Why Gein’s Case Endures in Popular Imagination

Several factors make Gein uniquely resonant:

- Scale and shock: The grotesque nature of the artifacts—lampshades, masks, and skin suits—created an image that lingered in headlines and dreams.

- Proximity and ordinariness: Gein lived among neighbors who described him as friendly and helpful, showing how horror could come from an unremarkable man.

- Psychological mystery: Gein’s motivations—maternal obsession, ritual, and necrophilia—defy neat classification, encouraging speculation and fiction writers.

- Media sensationalism: The mid-20th-century press amplified the scandal into a national phenomenon, constructing a bogeyman figure.

- Artistic appropriation: Writers and filmmakers transformed fragments of the case into enduring archetypes—the "mama's boy," the "skin-wearer," and the "psychopathic recluse."

Psychology, Forensics, and the Limits of Explanation

The Gein case raises uncomfortable questions about motive, capacity, and the nature of evil. Clinical observers noted symptoms that suggested psychosis: hallucinations, auditory phenomena, and disordered thought patterns. Unlike many serial killers driven by sexual sadism, control, or a calculated homicidal fantasy, Gein’s pathology included a mixture of necrophilia, obsessive-compulsive grave robbing, and a fixation on reconstituting maternal presence. Whether this constellation qualifies as psychosis, psychopathy, or a hybrid disorder has been debated for decades.

Forensics of the 1950s also shaped the investigation. DNA analysis did not exist; identification of parts sometimes had to rely on dental records, circumstantial evidence, and local knowledge. The numbers did not always add up: Gein admitted to nine grave desecrations, but twelve heads were recovered. Some body parts could not be definitively matched to known missing persons. That ambiguity fueled speculation about other, unconfirmed victims and about whether Gein might have murdered more people than he confessed to. It also made it more difficult for investigators and medical examiners to produce a neat accounting of his crimes.

Was Gein "Evil"?

Public reactions included moral judgments describing Gein as "evil." Clinicians and scholars are more cautious: they seek to explain behavior in terms of pathology, trauma, and social context. In documentary interviews, some people insisted he was born evil; others argued that his upbringing—dominated by a controlling mother and social isolation—created conditions for severe deterioration.

There is no simple answer. "Evil" is a moral category, not a clinical diagnosis. Yet the magnitude of Gein’s acts pushes people to moral language. Within forensic practice, the more useful approach is to analyze the sensorium of compulsion, the breakdown of reality-testing, and the role of fantasy in driving behavior. Gein’s mixture of maternal longing and mutilation suggests a symbolic economy: corpses and body parts were material expressions of psychological conflict. Whether this qualifies as insanity in a legal sense depends on capacity to understand right from wrong and to conform behavior to law; the courts judged Gein legally insane for murder after psychiatric assessment.

Plainfield’s Long Memory

Plainfield, a once anonymous village of only a few hundred residents, carried the stigma of Gein’s crimes for years. Locals did not want their town known for a gruesome museum of horror. They burned the house (or the house burned) and sold artifacts to carnival operators; but the site’s empty lot became a shrine for curiosity seekers for months. Headstones placed at Gein’s grave were repeatedly stolen by collectors and thrill-seekers—even in the 2000s there were reports of headstone fragments offered for sale on the internet. Such acts reveal a persistent cultural appetite for the tangible tokens of crime, even when those tokens disturb community memory.

Residents wanted to be remembered for the good people their schools produced—doctors, architects, and family-oriented citizens—not for one man’s monstrosity. Yet, as cultural historians note, small-town anonymity and the trauma of collective betrayal—when the neighbor you trusted is revealed as a killer—produce long-lasting scars. For Plainfield, the specter remained even as life went on.

Murderabilia, Wound Culture, and Ethics

Gein’s case is an early example of what contemporary scholars call "wound culture"—a public fascination with trauma and the physical remnants of crime. The carnival photos beside Gein’s car, the sale of his vehicle, and the later buying and selling of relics related to his grave and grave markers point to a market that treats real suffering as collectible. The moral questions here are straightforward yet unresolved: who has the right to possess and profit from items associated with atrocity? Should museums preserve such artifacts for historical and educational purposes, or does public display dignify the offender and re-victimize victims?

Some collectors rationalize their purchases as historical interest or as artifacts of criminology. Others fetishize macabre trophies. Lawmakers and platforms have struggled to regulate these markets. The debate continues, and Gein’s legacy plays an uncomfortable role in it.

Timeline Summary: Key Dates

- August 27, 1906 — Edward Gein born in La Crosse County, Wisconsin.

- c. 1914 — Family moves to the Plainfield farmhouse.

- April 1, 1940 — Father George Gein dies.

- May 1944 — Brother Henry dies during a brush fire; later controversy surrounds cause of death.

- December 29, 1945 — Mother Augusta Gein dies; Ed profoundly devastated.

- 1947–1952 — Period during which Gein confessed to regularly digging up graves and taking body parts.

- December 8, 1954 — Mary Hogan disappears (later found to have been murdered by Gein).

- November 16, 1957 — Bernice Warden is murdered; police discover the farmhouse of horrors; Gein arrested.

- November 21, 1957 — Gein pleads not guilty by reason of insanity and is declared unfit to stand trial.

- 1958 — The Gein farmhouse burned down prior to auction; Gein committed to Central State Hospital.

- March 1968 — Gein deemed competent to stand trial.

- November 14, 1968 — Found guilty of murder but legally insane; returned to institutional care.

- July 26, 1984 — Ed Gein dies of lung cancer at age 77; buried next to his mother.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How many people did Ed Gein kill?

Gein was convicted of two murders—Bernice Warden and Mary Hogan. He admitted to grave robbing nine corpses and to killing and dismembering those two women. The exact number of victims implicated by the remains found on his property (twelve heads and various body parts) created uncertainty—some remains could not be matched to known missing persons. Modern forensic limitations at the time mean there is still ambiguity about whether more murders occurred.

Did Ed Gein wear human skin?

Yes. Investigators found what was described as a "skin suit"—a torso and leggings fashioned from human skin. Gein reportedly donned this suit and wore flayed face-masks, sometimes performing acts in which he believed himself to be his mother. These behaviors were part of his confessed ritualistic attempts to become or recreate a female presence.

Was Gein the inspiration for Norman Bates and Leatherface?

Yes. Robert Bloch’s Norman Bates from Psycho explicitly drew on press reports about Gein’s maternal obsession. Tobe Hooper’s The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and Thomas Harris’ Buffalo Bill (in Silence of the Lambs) also contain elements inspired either directly or indirectly by Gein: the skin masks, the rural farmhouse setting, and the monstrous "everyman" facade.

Why did the farmhouse burn down?

The house burned down shortly before a scheduled auction in 1958. Official accounts suggested accidental causes related to neighbors burning debris, while locals speculated about deliberate destruction to prevent the site from becoming a morbid shrine. The ambiguity remains part of the case’s overall mythos.

Final Thoughts: Horror, History, and the Lessons of Plainfield

The Ed Gein case remains haunting for many reasons. It broke through mid-century notions of small-town safety and revealed a private pathology whose symbols—lampshades, masks, and skin suits—entered the lexicon of horror. It showed how grief, social isolation, and extreme upbringing can corrupt psychic development. It demonstrated the limits of forensic science of its day and awakened a national fascination with the "horror next door."

Yet beyond sensational headlines and cinematic adaptations, there are quieter, more human stories: the families of the victims, the small community of Plainfield coping with notoriety, and clinicians trying to understand a mind that oscillated between childlike dependence and the capacity for brutal acts. Gein’s story is not merely a grotesque tableau for fiction; it is a reminder of how social context, mental illness, and unchecked compulsions can converge into real-world catastrophe.

As a documentary narrator, as someone who has sifted through the official records and interviewed residents and professionals, I can tell you this: Ed Gein remains one of the most disturbing figures in American crime precisely because he blurs ordinary life and unimaginable atrocity. It is one thing to read about monstrous figures who feel alien; it is another to discover that an apparently ordinary neighbor harbored such darkness.

Finally, it is worth asking what responsibility we have as consumers of true crime. We are drawn to the strange and the macabre, but we must balance curiosity with respect for victims and communities. The story of Ed Gein is not entertainment—it's a cautionary tale about human vulnerability, the consequences of isolation, and the ways in which grief can devour a life.

Further Reading & Resources

If you want to learn more about the case and its cultural impact, consult primary-source materials such as police reports, court transcripts, and contemporary newspaper coverage. Scholarly analyses in forensic psychology also provide useful frameworks for understanding the interplay of psychosis, developmental trauma, and criminal behavior.

Thank you for reading this comprehensive account. How did this happen? And why? The answers are imperfect, but the detailed facts and the historical record help us confront the horror with clarity, if not comfort.

0 Comments